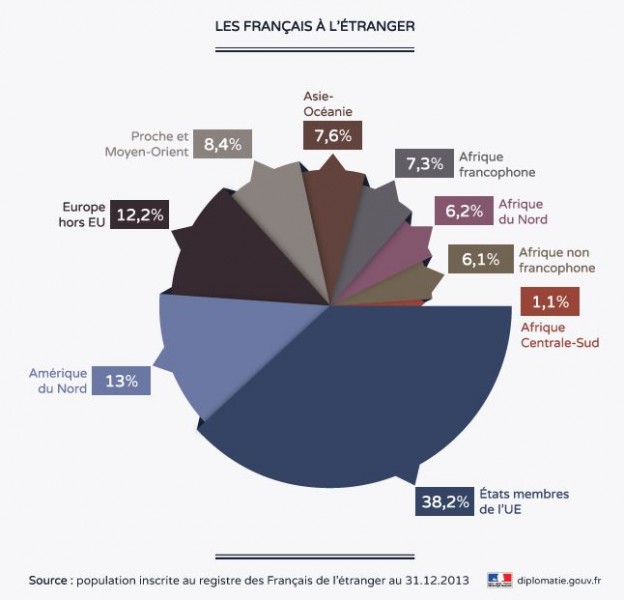

Total of French citizens abroad by continent as compiled by the Foreign Affairs Ministry – Public Domain

The immigration debate has increasingly polarized public opinion in France over the past few years. The rise of the far right, such as the National Front party, in recent elections catalyzed an anti-immigration rhetoric that seems to permeate into the more moderate conservative parties. The most notorious stories involved the “pain au chocolat” [fr] (chocolate croissants) affair, in which the leader of the opposition JF Copé stated that he was distraught knowing that children in some districts get harassed by Muslim youngsters [fr] for eating chocolate croissants during Ramadan.

The push for more restrictive immigration policies that would limit unqualified (without high school diploma) candidates to migrate to France has found echoes [fr] in the current progressive government. In fact, a book published by philosopher Alain Finkelkraut called “L'idendité malheureuse” (The Unhappy Identity) attempts to justify imposing more strict regulations on immigration in order to protect the French identity [fr]:

Les autochtones ont perdu le statut de référent culturel qui était le leur dans les périodes précédentes de l’immigration. Ils ne sont plus prescripteurs. Quand ils voient se multiplier les conversions à l’islam, ils se demandent où ils habitent. Ils n’ont pas bougé, mais tout a changé autour d’eux. […] Plus l’immigration augmente et plus le territoire se fragmente.

The “original” French people have lost the status of cultural reference, a status they held in earlier periods of immigration. They are no longer the normative reference. When they see increased conversions to Islam, they wonder where they live. They have not moved, yet everything has changed around them. […] The more immigration increases, the more the nation becomes fragmented.

Frederic Martel, director of IRIS, a research institute on international relations, explains why Finkelkraut's discourse is misguided [fr]:

Il y a, c’est certain, une forte anxiété dans la France d’aujourd’hui. Mais pourquoi caricaturer tous les «étrangers» comme s’ils ne voulaient ni s’intégrer ni accepter le passé de la France? Que sait-il des Français de deuxième et troisième génération? De leur langue, de leur culture? De l’énergie créatrice des quartiers? […] L’identité française, pourtant, n’est pas malheureuse. Elle bouge, elle change, elle se cherche, elle fait des allers-retours avec son passé. Et tous ceux qui pensent qu’exalter «l’identité nationale» permettrait de sortir des difficultés sociales et économiques que nous traversons se trompent.

There is certainly a lot of anxiety in France today. But why caricature all foreigners as if they do not want to fit in nor accept the history of France? What does [Finkelkraut] know of France's second and third generation of immigrants? Their language and their culture? The creative energy they bring to their neighborhoods? […] The French identity is not an unhappy one.”It moves, it changes, it goes forward, backward towards the past, then forward again. Anyone who thinks that exalting “national identity” would solve our social and economic challenges is just kidding themselves.

The natural counterpoint to the rising anti-immigration policies is the fact that there is a rising number of French citizens who have chosen to live abroad. Christian Lemaitre from think tank Français-Etranger (French Abroad) points out that the total number of French citizens outside of France is quite important and might be larger [fr] than the official total shared by the French Foreign Affairs Department:

En dix ans, la population française établie hors des frontières se serait accrue de 40% soit une augmentation de 3 à 4% par an et un total de plus de 2 millions de Français installés à l'étranger. Estimation seulement car l'inscription au registre mondial n'est pas obligatoire. Le think tank francais-etranger.org pense que ce chiffre serait beaucoup plus proche de 3 milions. Pourquoi sont-ils partis ? 65% des expatriés affirment rechercher une nouvelle expérience professionnelle et près du tiers, une augmentation de revenus. Le désir de découvrir un nouveau pays est évoqué devant les motivations professionnelles ou linguistiques.

In ten years, the French population abroad have seen an increase of 40 percent, an increase of 3 to 4 percent per year, and a total of more than two million French now live abroad. This is only an estimate because sign up in the consulate's register is not mandatory. The think tank French-etranger.org thinks that number would be much closer to three million people. Why have they left France? 65 percent of expatriates say that they were looking for new work experience and nearly a third of them wanted a better income. The desire to discover a new country is also mentioned first, before any professional or linguistic motivations.

Indeed, the viewpoint on immigration differs when seen from French citizens outside France.

In fact, despite the popular belief that French citizens living abroad were mostly conservatives, their votes have increasingly leaned towards the left in the past decade. Cécile Dehesdin [fr] explains:

Depuis 1981, elle a gagné plus de vingt points chez les Français de l'étranger, et l'écart avec son score national y était de moins d'un point en 2007 (46,01% contre 46,94%)

Since 1981, [the left] has won more than 20 points in French from abroad voting and the gap with the national score there was less than one point in 2007 (46.01 percent against 46.94 percent).

Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, an analyst, adds [fr]:

C’est un public qui est plutôt au centre-droit qu’à droite et pas du tout à l’extrême-droite, plutôt droite humaniste que Droite populaire, et l’écart avec la gauche est de moins en moins important

This is a voting group that is more center-right and right, but not attracted at all to far-right views; it is rather leaning towards progressive right than radical right, and the gap with the left has become less and less important

Additionally, the experience of living abroad seem to have given many French citizens a different perspective. Etoile66, in Toronto, opines [fr]:

Ma France pourrait regarder vers ces pays où les habitants parlent plusieurs langues sans aucun problème et circulent à l'aise dans le monde, alors qu'elle a dressé ses habitants à avoir peur de ce qu'ils appellent la “mondialisation”. La peur ressentie par bon nombre de mes compatriotes devant “l'étranger” en général et la “mondialisation” en particulier, ne serait plus s'ils avaient confiance en eux. Celui qui a confiance n'a pas peur de l'autre ni de l'étranger, ni du monde, bien au contraire, il échange dans le respect mutuel.

The France I want to see should look to those countries where people speak different languages without any problems and move at ease in the world. So far, France has only taught its people to be afraid of what they call “globalization”. The fear felt by many of my countrymen of “foreigners” in general and “globalization” in particular, would vanish if they had confidence in themselves. People who have self-confidence do not fear the “other”, “foreigners”, nor the world. On the contrary, they interact with them with mutual respect.

1 comment