This article was written by Ana Arana and Daniela Guazo for Fundación MEPI. This is the second part in a series about crime reporting in Honduras. You can find the first part here.

When reading most Honduran newspapers, readers go away with little understanding of what is occurring in the country. Most crime stories are written without context or explanation and are accompanied by bloody, gory pictures. Local media write these crime stories purposely, as a safety mechanism because of entrenched fear and trepidation among local reporters and editors, according to interviews with reporters and editors and a review of various newspapers in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula by Fundacion MEPI, a regional investigative journalism project based in Mexico City.

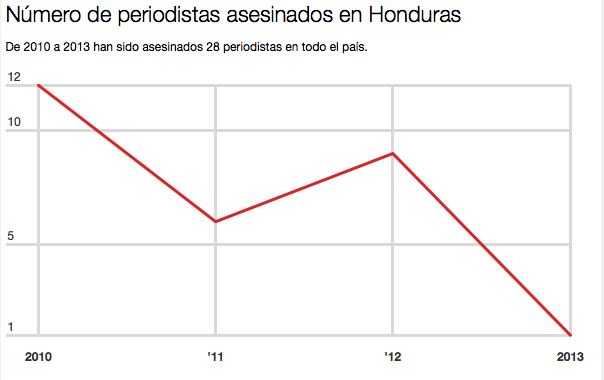

Number of journalists killed in Honduras. From 2010 to 2013, 28 journalists were killed in the whole country. Click on image to visit article with interactive graph

MEPI's analysis found that the news media reports extensively about youth gang criminal activities, but they seldom write about the presence of international organized crime groups and their connections in Honduras to the security forces and to business and political sectors. In private interviews, editors, reporters and news analysts, who asked for anonymity recounted strategies applied in newsrooms to protect their staff of violence. Twenty-nine journalists have been murdered in Honduras in the last four years, with 16 of them were killed because of their work, according to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, CPJ. MEPI has completed similar investigations on how the media works under threat of violence in the Mexican regional press.

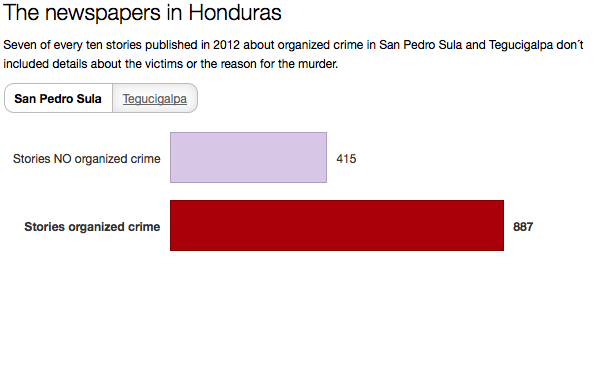

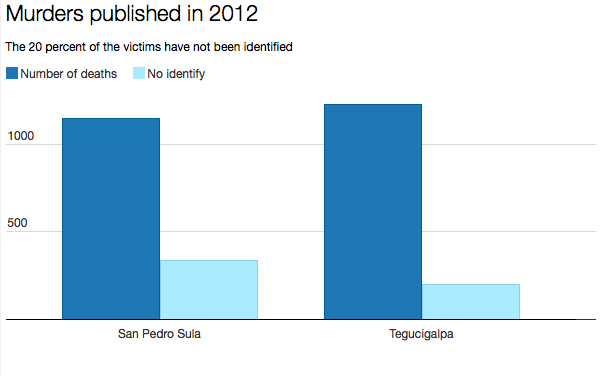

The content analysis by MEPI showed that seven out of ten stories about crime published in both San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa media did not include details about the victims, nor the possible reasons for the crime. Gruesome pictures were often spread across the pages with headlines such as: “Found dead after visiting his Mother,” “Three men are executed and placed in plastic bags,” or “Transvestite is taken out of his house and killed.”

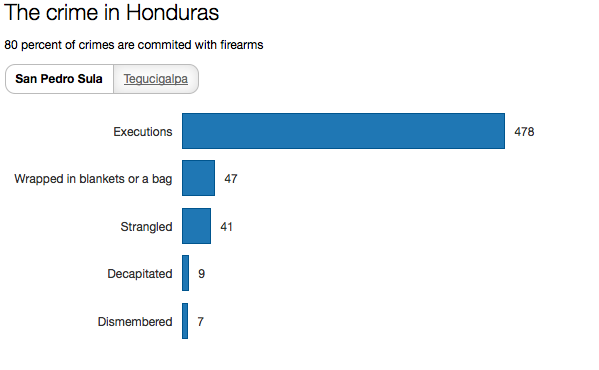

MEPI's content analysis found that the media has been correctly reporting on a wave of violence of great proportions and premeditation. According to the stories, 80 percent of the crimes were committed with firearms and 20 percent of the victims were tortured before and after they were killed. Many of the bodies were found tied up and packed inside black garbage bags, a practice also favored by Mexican organized crime groups.

In March 2012, newspaper accounts described an escalation in the number of victims found decapitated or with their bodies cut to pieces. None of the stories, however, provided reasons as to why the new killing method was introduced in Honduras. A crime reporter told MEPI that the new killing methods could be tied to the Mexican organized crime group, Zetas, former military special forces-turned bandits, who built up a reputation for their brutality in killing opponents, and who have a presence in Central America. “About a year and half ago, bodies in plastic bags started appearing. The government won't accept it is linked to the Zetas,” he said.

Like in Mexico, criminal groups also leave messages at the crime scenes. Some of the messages are carved out in the victims’ bodies. Other messages are scribbled by hand in cardboard signs that are placed next to the bodies. In 2012, several victims were found in both Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula with a hand or foot missing. The message was cryptic to the uninitiated. But a criminal investigator in El Salvador said that often those mutilations have specific meanings. A missing hand means the victim stole; a missing foot, he fled. Both are messages to the victim's friends.

In Mexico, several media leaders were critical of the media when it published the messages left at crime scenes, and most newspapers and television news programs have stopped publishing or broadcasting them. The media agreed that they were becoming messengers in criminal groups’ vendettas. The Honduran press, however, continues to publish the messages.

More than 70 taxi and bus drivers were killed in 2012. They are the two top jobs and occupations that are high risk in Honduras today. But MEPI did not find any stories explaining to readers why these jobs have a higher probability of violence on the job. The stories also do not explain if the government has any program to improve security for workers in these occupations.

Similarly, five out of each 10 murders in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula in 2012 were carried out by men who rode as passengers in motorcycles, although there is a law prohibiting two riders in a motorbike.

Stay tuned for the third and final instalment in this series about crime reporting in Honduras.

3 comments

Bloody city.