This article written by Coletivo Catarse was originally published by Brazilian investigative journalism organization Agência Pública on 30 October 2013 under the title “Nem tão limpa, nem tão barata” (Neither really clean, nor really cheap).

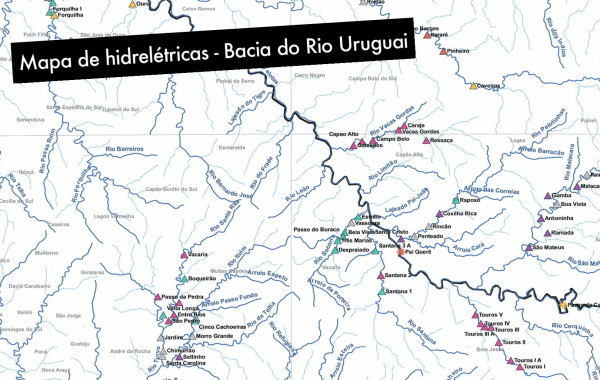

The largest hydrographic basin in the southern Brazil is studded with hydroelectric plants. What used to be a complex system of rapidly flowing rivers has now become an almost never ending series of wide and deep lakes. And it is exactly in the last stretches of Uruguai river, which makes boundary with Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, within the Brazilian territory, where the original environmental features are still preserved, that the federal government is planning to allow the installation of more plants, meaning more dams. It won't consider the potential impact of trampling over social, economic and environmental rights. “The Brazilian people must be made aware that so-called clean and cheap energy does not exist”, warns professor Célio Bermann from the University of São Paulo.

We traveled the paths along the Uruguay River on the border between the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina in order to refine our views on the issue. The result of this journey is a video report called “Barragem” (Dam, in Portuguese), available for viewing below.

With the ever-accepted explanation that it is a sustainable natural resource, the granting of power generation to investors is decided according to those who propose the lowest price for energy sale. Standing on the side of those who believe the hydroelectric plants make economic sense is Ronaldo Custódio, the Engineering and Operation director of Eletrosul (a subsidiary of the Brazilian energy company Eletrobras). He states:

E se chega no menor preço pelo custo do investimento, a energia que cada fonte produz e o custo do dinheiro que tu pegas para realizar o projeto.

One comes to the lowest price by the cost of the investment, the amount of energy that each source produces and the cost of the money borrowed in order to carry out the project.

It happens, though, that a river is not a chute or a drain, but a live organism connected by a system of flows upstream and downstream. For Rafael Cruz, the coordinator of the study “FRAG/Rio” on the integrated environmental impact of the Uruguay River Basin, the first question that should come to mind as one thinks of installing dams in a river is what capacity it holds for withstanding hydroelectric plants. Rafael Cruz criticizes:

Quando se faz a contabilidade tradicional de uma usina hidrelétrica, e não se verifica a fragilidade do rio devido aos impactos ambientais, pode parecer limpa.

When one applies the traditional accounting concepts to the project of a hydroelectric plant, and one does not check on the frailty of the river as regards the environmental impacts, it may seem a clean choice.

By observing the sites proposed for the hydroelectric plants, talking to the people affected by the projects, challenging the enterprises involved, consulting experts on the subject and pouring through the available data, our team tried to investigate and come up with an answer as to how these externalities, which aren't part of the focus when decisions on energy policy are made, are being taken care of.

In the closing remarks of the documentary, researcher Rafael Cruz states that it is essential to simply compare the budgets of the construction and the energy that new developments will generate, in order to define priorities:

A diferença é tão absurda que a gente acaba por entender porque é que estes programas nao têm eficácia e a gente continua tendo que devastar florestas, remover pessoas do seu ambiente, para construir hidreletricas que sao altamente impactantes e que talvez nao precisassem ser construídas se realmente uma política de economia de energia fosse realmente efectuada de uma forma eficaz.

The difference is sometimes so absurd that we end up understanding why these programs are not efficient and thus we need to keep devastating forests, removing people from their environment, in order to build more hydroelectric power plants that are highly impactful and that perhaps wouldn't need to be built if a real economic policy for energy was really performed in an effective way.