A young Vladimir Putin, imagined as a young Mr. Burns from The Simpsons, by Egor Zhgun, YouTube screenshot.

The Russian pension system is poised for a new round of reforms that will return the program to an entirely pay-as-you-go design, at least for 2014. The decision to freeze new deposits into laborers’ retirement market accounts appears to be a preemptive effort to spare the federal budget, amidst growing economic stagnation. As the government scrambles to boost available short-term funds for pension payments, ordinary Russians have denounced the move as “confiscatory.” Indeed, reactions [ru] were so ubiquitously negative that even Vladimir Putin found it necessary [ru] to exclaim publically, “The government isn’t discussing the confiscation of these savings, God forbid!” (The formal justification for freezing the market accounts is re-vetting private fund managers.)

Putin’s assurances seem to have persuaded few in the RuNet’s economically savvy ranks, where confidence is low that the state will follow through on its promise to reimburse lost income to individuals’ retirement savings accounts. (The Ministry of Finance has pledged [ru] to return the money, along with 7% interest, though the market accounts’ average profits [ru] range from 8-9%.) In fact, pessimism isn’t limited to people who claim to understand the pension system, which has grown even more convoluted in recent years. Many Russians seem to believe that the complexity of the pension system [ru] is intended, at least in part, to exploit people’s confusion.

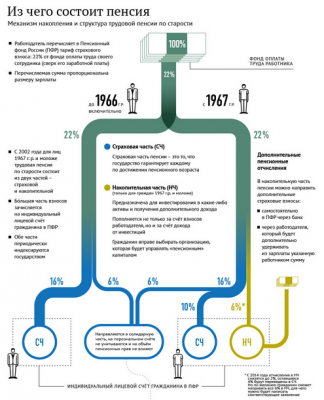

For the last decade, Russians have paid 22% of their income [ru] into the country’s retirement program. Of that money, 6% funds the fixed basic payment collected jointly and guaranteed to all pensioners. (In January 2013, this amount was 3,610 rubles (112 USD) per month.) The other 16% is deposited into individual accounts, which function on a PAYG basis, like the basic payment deposits. The individual accounts are recorded separately, however, allowing people to earn slightly higher pensions, if they had higher salaries when they were in the workforce. When someone stops working, their monthly benefits are calculated by dividing the total value of their individual account by 228 (the number of months a person is expected to live, after retirement), and adding 3,610 rubles. This is the system that defines pensions for Russians born before 1967—the last true Soviet generation.

For Russians born in 1967 or later, the government has toyed with a market-based savings program to boost retirement funds. According to this system, only 10% of the income tax flows into the individual accounts described above. The remaining 6% is invested in the economy, and individuals are allowed to choose who manages the money: private parties (vetted by the government) or the state development bank Vnesheconombank. (People have to petition for private management. By default, the state bank takes charge of the accounts.) Last year, officials revised the program, reducing the default contribution into market accounts to just 2%, requiring individuals to petition to have the full 6% deposited.

According to legislation [ru] submitted to the parliament on Monday, September 30, 2013, the government now wants to remove entirely people’s freedom to contribute to market savings accounts, at least for 2014. Additionally, the state plans to redistribute all privately managed deposits in 2013 to Vnesheconombank, which averages slightly lower profit returns.

About one in four of the latter, post-1967 group of pensioners (20 million people of 76.5 million) currently entrusts a market savings account to private managers. Many of these Russians—the people who show faith in the country’s stock market—represent [ru] the confident young professionals who pervade the Russian Internet today. Despite maturing in the turbulent 1990s, an increasing number in this category have been willing to risk a chunk of their pension payments on potential future rewards. If these enterprising individuals weren’t already ill-disposed toward the Kremlin and United Russia, the (albeit temporary) seizure of their market deposits will certainly bring many new recruits to the anti-government camp.

Popular reactions online make it clear that anger about the “confiscation” of pension savings merges easily with preexisting, populist criticisms of the Putin government. Even though it only makes up about 40% of the money accumulated by one year of Russian pensions’ market savings accounts, bloggers have blamed [ru] the Sochi Winter Olympics’ 99-billion-ruble price tag [ru] for poisoning the federal budget and necessitating the raid on pensions. Political analyst Evgeny Gontmakher has exploited apparent miscommunication between Putin and the Finance Ministry to argue [ru] that the President is losing control of his administration. Writing on LiveJournal, others have adopted anti-corruption rhetoric (popularized by Alexey Navalny), asking [ru] if the Pension Fund’s palatial office buildings [ru] might be partly to blame for the system’s financial woes.

Writing on Facebook [ru], on October 1, 2013, economist Alfred Kokh said Russia’s pension system is a “ticking time bomb.” The government’s only options, he says, are to raise the retirement age, freeze benefits, and transition to a savings account system (like the one it just suspended). Such measures, however, are bound to cost the Kremlin popularity points. Before the 2011-2012 “Winter of Discontent,” Putin’s most serious confrontation with mass demonstrations was the protest against the monetization of pension benefits in 2005. How bad does Russia’s current pension crisis have to get before people take to the streets again?

1 comment

Transparent Russian Online 6 Month License

[…] human connection. For those seeking a wider picture, Zuckerman highlights the ch […]