This post is part of our special coverage of Brazil's Vinegar Revolt

[All links lead to Portuguese-language pages, except when otherwise noted.]

When protests sprang up all over Brazil earlier this year, media collective Coletivo Nigéria of Fortaleza also took to the streets, cameras in hand. Filmmaker Pedro Rocha explains:

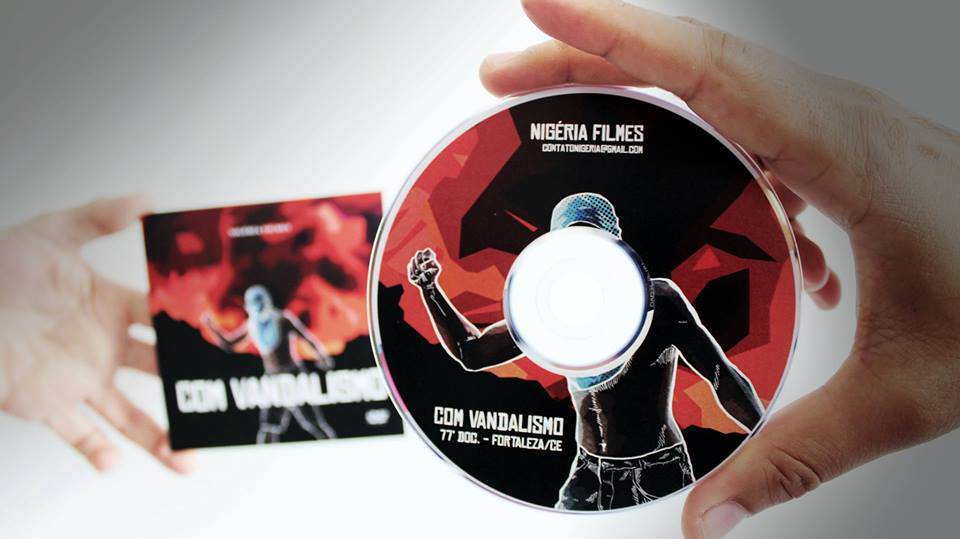

“We didn't know what would come of our coverage of the protests, we only knew that we had to be there,” explains Pedro Rocha about the documentary Com Vandalismo. Watch the film through the article published in August 2013 by Global Voices.

Começamos filmando pelo dever de registrar o que estava acontecendo. Não fazíamos a menor ideia no que aquilo ia dar.

We started filming because of the necessity to record what was happening. We didn't have the slightest idea what was going to happen.

This was the start of their recent project, according to Pedro Rocha, one of the four journalists that graduated two years ago and formed the collective, along with Roger Quentin, Yargo Gurjão, and Bruno Xavier. The result was the popular documentary “Com Vandalismo” (Vandalism) [en], which narrates the events of that period in the city of Fortaleza, with a critical focus on the mainstream media discourse constructed with regards to “vandalism.”

In an email interview with Global Voices, Pedro Rocha explains in more detail about this experience and reflects on the possible directions that online communications may take in the country after the protests.

Global Voices (GV): Do you think that with the protests and the intensive use of social networking tools, the Brazilian citizen media took a step forward?

Pedro Rocha (PR): Talvez a gente precise esperar um pouco mais. Ver como isso vai funcionar na Copa, por exemplo. Para usar uma palavrinha mágica sempre que se fala de megaeventos: precisamos ver qual será o “legado” desses protestos para a comunicação. De todo modo, se o ditado que diz que “a necessidade faz o homem” estiver certo, provavelmente esse amadurecimento irá se concretizar.

Até agora, o que vimos foram as pessoas correndo para as redes sociais em busca de informação, porque só com a grande mídia não dá – ainda mais agora que a relação entre essa mídia e os manifestantes está cada vez mais desgastada. Muitos manifestantes não concedem entrevistas a eles (se é que um dia essas entrevistas foram solicitadas) e hostilizam os repórteres de algumas emissoras. Por outro lado, a mídia alternativa, independente ou cidadã, seja qual for o nome, é quem está criando e ocupando esse espaço.

Perhaps we need to wait a little longer. To see how this will work during the World Cup, for example. To use the magic word that is always present when there is talk of mega-events: we need to see what will be the “legacy” of these protests for the media. Whichever way it goes, if the saying “necessity makes the man” turns out to be true, this progress will probably become concrete.

Until now, what we saw were people running to social networks in search of information, because just following the mainstream media isn't enough – even more so now that the relationship between this media and the demonstrators has become strained. Many protesters don't give interviews to them (if one of these interviews were to be requested) and are hostile towards reporters of these large networks. On the other hand, the alternative media, independent or citizen-based or whatever the name may be, is what is creating and occupying this space.

GV: How do these changes on the political and media landscape affect the future of what you as a collective are doing?

Bruno Xavier, one of the members of Nigeria, in action during the exhibition of one of the documentaries by the collective in a neighborhood restaurant. Photo used with permission.

PR: Primeiro, estamos nos questionando mais do que nunca sobre o nosso trabalho, sobre as ideias que nos orientam, sobre como devemos nos posicionar nessa história. Em segundo lugar, vem a forma como nos organizamos como produtora e/ou coletivo.

A “produtora” Nigéria trabalha com comunicação institucional pra movimentos sociais e terceiro setor principalmente. Nós sempre guiamos politicamente nosso trabalho. Porém, isso às vezes pode entrar em conflito com as exigências da cobertura das manifestações, quando atuamos mais como “coletivo” – de forma voluntária, por assim dizer. Quer dizer, às vezes temos que priorizar uma coisa ou outra ou nos dividir e sacrificar um pouco cada lado. Além disso, temos nossa produção jornalística propriamente dita, que requer um tratamento diferente dos vídeos institucionais ou mesmo dos vídeos das manifestações.

Na nossa opinião, todas estas diferentes formas de comunicação são importantes e se complementam, mas precisaremos cada vez mais pensar na forma como sustentar esses trabalhos. Por exemplo, a partir da repercussão Com Vandalismo – realizado sem nenhum financiamento e com a colaboração de várias outras pessoas além dos integrantes da Nigéria – estamos planejando uma forma de financiar a cobertura da Copa no próximo ano.

First, we are questioning more than ever the nature of our work, about the ideas that guide us and how to position ourselves in this story. Second, we question the way that we organize ourselves as producers and/or as a collective.

The media production collective Nigéria works primarily with institutional communication for social movements and the not-for-profit sector. We are always politically guided in our work. However, sometimes it possible to be in conflict with the demands of covering the protests, when we are acting more as a “collective”- in a voluntary way, as it were. In other words, we have to prioritize one thing or another, or we split up and sacrifice a little bit on each side. Aside from this, we have the journalistic production itself, which requires a different treatment than institutional videos or videos of the protests.

In our opinion, all of these different forms of communication are important and complement each other, but we need to think more and more about how to sustain these efforts. For example, because of the response to “Com Vandalismo” – filmed without any financial support and with the collaboration of many other people outside of Nigeria – we are planning to find a way to finance the coverage of the World Cup next year.

GV: In the documentary, you appear for a moment with some students of a social communications program. Has there been some exchange between the program and Nigeria?

PR: Sou professor do curso de jornalismo de uma faculdade particular aqui de Fortaleza. E já tinha convidado dois estudantes de lá, o Franzé e o Leandro, para serem bolsistas em um outro projeto da Nigéria sobre Direito à Moradia. Nós estávamos mapeando as ocupações irregulares em Fortaleza quando os protestos estouraram no país. Nessa história, eles acabaram compondo a equipe. Estiveram em todos os quatro dias que o documentário registrou e, no último, o Leandro acabou sendo detido comigo, depois de sermos encurralados pelo Batalhão de Choque. Não fomos para a delegacia porque a presidente do Sindicato dos Jornalistas do Ceará passou no local exatamente na hora.

I am professor in the journalism department of a private college here in Fortaleza. And I have already invited two students from there, Franzé and Leandro, to be scholarship participants in another project by Nigeria about the movement for Rights to Adequate Housing. We were mapping the irregular occupations in Fortaleza when the protests erupted in the country. In covering this story, they ended up becoming a part of the team. They were with us the whole time during the four days in which the documentary was filmed, and Leandro ended up getting arrested with me, after getting cornered by the riot police. We didn't go to the police station because the president of the Journalist's Union of Ceará passed by at that exact moment.

GV: What are the differences between work with Nigéria and your other professional experiences in the media?

PR: Os quatro integrantes da Nigéria têm percursos profissionais diferentes, mas, com exceção de um, tivemos passagens mais curtas ou mais longas pelos maiores grupos de comunicação do Ceará. E existe uma primeira grande diferença, que é a diferença entre ser empregado de uma grande empresa e ser sócio de seus amigos numa produtora. É verdade que isso impacta também na sua estabilidade financeira, mas isso é compensado por outros ganhos, como a ausência de hierarquia.

From left to right: Pedro Rocha, Yargo Gurjão, Bruno Xavier and Roger Quentin. Photo used with permission.

Por exemplo, a falta de hierarquia faz com que estejamos a todo momento debatendo – agora mesmo estamos tendo que encarar na prática conceitos como o “equilíbrio” em nossa produção jornalística, já que nos identificamos com as posições dos manifestantes, mas também queremos nos manter como um espaço em que o diálogo e o debate sejam possíveis. Esse tipo de organização nos dá também a liberdade de escolhermos no que queremos apostar e a responsabilidade de assumirmos esse risco. O Com Vandalismo foi um caso desses. Depois de tudo, alguns outros projetos atrasaram, foram deixados temporariamente de lado, mas valeu a pena.

The four members of Nigeria all have different professional trajectories, but, with the exception of one, we have had short or longer periods of working for the larger media organizations in Ceará. And a major difference exists, which is the difference between being employed by a large company and being an associate of your friends as a producer. It is true that this also impacts one's financial situation, but this is compensated by other gains, such as the absence of hierarchy.

For example, the lack of hierarchy means that we are debating all the time – right now we are having to confront concepts such as “balance” in the practice of our journalistic production. We have already identified with the position of the demonstrators, but we also want to maintain a space where dialogue and debate are possible. This type of organization also gives us the freedom to choose what we want to risk and the responsibility of assuming this risk. “Com Vandalism” was one of these cases. After everything, some other projects were delayed and pushed temporarily to the side, but it was worth it.

GV: What were the main challenges in covering the protests?

PR: Tirando o fato de que não conhecíamos gás lacrimogênio e bala de borracha, nem exatamente sabíamos como se portar diante daquele tipo de situação de confronto, o maior desafio a meu ver foi se orientar naquela revolta. Saber o que filmar, quem entrevistar, perceber o que estava em jogo – basicamente entender o que estava acontecendo no país. Se ainda hoje é difícil entender isso, não pense que foi mais fácil para quem estava lá na Alberto Craveiro, sob um sol infernal, no meio de um mar de gente correndo e tossindo gás lacrimogênio. Talvez por isso a repressão policial tenha se transformado numa pauta por si só, por ser um elemento imediato, inquestionável e, no final das contas, aglutinador, apesar de o objetivo ter sido a “dispersão” dos manifestantes. Talvez por isso também escolhemos nos apoiar num ponto específico, o “vandalismo”, para seguirmos documentando, sem nos perdermos em julgamentos sobre a história.

Apart from the fact that we weren't familiar with tear gas and rubber bullets, nor did we exactly know how to behave in the face of that kind of confrontation, the biggest challenge from my point of view was orienting oneself in the revolt. Knowing what to film, who to interview, perceiving what was at play – basically understanding what was happening in the country. If today it is still difficult to understand this, don't think that it was any easier for those who were there at Alberto Craveiro under an infernal sun, in the middle of a sea of people running and coughing up tear gas. Perhaps that's why police repression has become an issue in itself, if only because it is an undoubtedly immediate and, after everything, unifying element, in spite of its purpose to “disperse” protesters. Perhaps this is also why we choose to support a specific point, that of “vandalism”, to continue documenting without losing ourselves in judgement about the story.

GV: What do you as a group think about the collectives that emerged during the protests, such as Midia Ninja [“an alternative journalism phenomenon that emerged from the protests in Brazil”, Journalism in the Americas blog reported]?

PR: A Mídia Ninja é, sem dúvida, o maior fenômeno dessa comunicação que ganhou força com os protestos. As transmissões ao vivo, pra mim, são o elemento mais revolucionário nessa história toda. Em junho, você podia assistir o helicóptero da Record News sobrevoando São Paulo ou o Rio de Janeiro, ao mesmo tempo em que acompanhava um cara correndo pelas ruas com um celular entrevistando os manifestantes. Se você demorasse um pouco mais nessa dupla cobertura, iria perceber que algumas coisas na transmissão da TV estavam equivocadas.

Hoje nós temos transmissão ao vivo pela Internet aqui em Fortaleza e imagino que em quase toda cidade em que o 3G dê conta do serviço. Particularmente gosto de acreditar que os ninjas viraram uma espécie de confraria ou, simplesmente, uma rede, independente do grupo Mídia Ninja até. Por outro lado, existem coletivos, como a Nigéria, que não fazem cobertura ao vivo, mas registram e postam no mesmo dia ou no dia seguinte alguns vídeos, já com alguma edição e com uma qualidade melhor de imagem. Esse é outro tipo de cobertura que se junta às transmissões, aos relatos pessoais no Facebook, às charges de ilustradores independentes etc.

Se o Brasil tivesse uma TV pública de qualidade e um sistema de comunicação realmente democrático, ainda assim esse tipo de ação seria necessário. Ou seja, diante do monopólio comercial da comunicação brasileira, essa comunicação dos ninjas e dos coletivos é questão de sobrevivência e esperamos que só se fortaleça daqui pra frente.

Midia Ninja is, without a doubt, the biggest phenomenon of these forms of communication that gained support with the protests. The live transmissions, for me, were the most revolutionary element in this whole story. In June, you could watch coverage from the Record News helicopter flying above Sao Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, and at the same time that you could see a guy running through the streets with a phone interviewing demonstrators. If you watched even a little bit of this double coverage, you were able to perceive that some things in the TV coverage were wrong.

Today we have live transmission by way of the Internet here in Fortaleza, and I imagine there is the same in every city that has 3G coverage. I particularly like to believe that the ninjas became their own kind of brotherhood, or simply a network independent of even Midia Ninja. On the hand, collectives exist, such as Nigeria, that don't do live coverage, but instead film and post videos on the same or on the following day that have been edited and have a better image quality. This is the other type of coverage that brings together all transmissions, from personal accounts on Facebook to cartoons by independent illustrators, etc.

If Brazil had quality public TV and a truly democratic system of communications, this type of action would still be necessary. In other words, in the face of the commercial monopoly of Brazilian communications, this type of coverage by the ninjas and collectives is a matter of survival, and we hope that it will be strengthened from here on out.

This post is part of our special coverage of Brazil's Vinegar Revolt

1 comment

Thanks for this interview, I really loved the documentary.