The Indian Memory Project website describes itself as “a visual and oral history of the Indian subcontinent via family archives”. Started in 2010 by photographer and designer Anusha Yadav, it is an online, curated collection of photos contributed by members of the public. Contributors also tell the story behind each image.

Global Voices spoke to Anusha Yadav about what inspired her to set up the website, and how it works.

Global Voices (GV): What gave you the idea to start the Indian Memory Project?

Anusha Yadav (AY): Photographs have always grabbed my attention in a museum, in books or at someone's house. I was brought up in Jaipur, the royal capital of Rajasthan, although during my childhood all that was left behind were well-maintained and guarded structures and palaces of heritage. My own school, the Maharani Gayatri Devi School, had the queen’s own museum of personal photographs and accessories. When I visited my friends’ homes I would gaze wide-eyed upon living room tables and walls embellished with images of royals, elites or just simple traditional families.

At my own home, we would spend holidays repeatedly projecting my late father’s images on the wall, photographed when we lived in London, UK and Portland, USA. I would relive what I considered the happiest of my memories, insisting that my mother repeat all the adventures of our lives there. Paintings did not inspire me as much as photographs. Paintings were imagined, fictional even, but photographs were real and much more exciting because they were closest to the truth. With every image that made me pause, I would find myself travelling in time, wondering about the subjects and their lives and experiences.

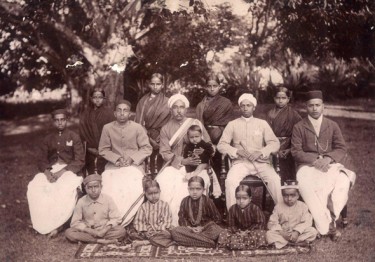

Image contributed to the Indian Memory Project by Laxmi Murthy, Bangalore: “My great-grandparents (right) with the Chennagiri family, Tumkur, Mysore State (now in Karnataka), circa 1901.” Used with permission.

From 1992 to 2006, I attended the National Institute of Design at Ahmedabad, worked with several graphic design and advertising firms, and travelled and lived in different parts of the world and of India. Photography and images by then had become exceptionally important to me. I felt that with photographs I understood the world better.

In 2006, I attended the University of Brighton to study for a masters in photography, but lack of finances made me abandon it after a semester and return to India. In 2007, I continued working as a photographer and book designer, and I also began suggesting ideas for coffee table photo books to publishers. One of the ideas came from an observation that I had made many years before, that almost everyone in this world owns at least one personal photograph. In India most common family photographs are of weddings, an event that is always photographed. If people can’t afford that, the newlyweds are photographed right after the wedding. Both types of photos act as proof of marriage. To explore and document India's immensely diverse culture and identity through these very personal images of weddings, attire, traditions and forgotten ceremonies seemed a fantastic book in the making.

As if by divine design, Facebook had just introduced a photo-sharing platform, and it was to mark the beginning of crowdsourcing images and stories. I started a group and called for images from family, friends and the public, and asked that along with these images they give some details. The contributors themselves were one step ahead and wrote more than just wedding stories. They mentioned events that immediately formed categories in my mind, such as the India/Pakistan/Bangladesh partition, the British empire, migration, love, marriage and friendships, battles and world wars, professions and businesses, and ordinary and extraordinary family lives. Each photograph came with a riveting anecdote about lives, families, grievances and accomplishments, emerging as a collective story of a nation and a subcontinent. The idea behind Indian Memory Project had snapped into place.

Image contributed to the Indian Memory Project by Sawant Singh, Mumbai: “My grandmother Kanwarani Danesh Kumari, Patiala, Punjab, circa 1933.” Used with permission.

GV: Are there limitations to the material you accept?

AY: All Images and stories must be from before 1991. That is when images – because of one-hour photo booths, or later as digital – began to become less deliberate. It doesn't mean the images from the 21st century shouldn't be documented, but we do have two centuries to cover before that. I am also more interested in deliberate images, as they make for better and far more accurate stories.

GV: Do you receive contributions from outside of India?

AY: Yes, I do. So far I have received around 20 images and stories from people abroad, from places such as South Africa, Australia, the UK, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the USA. The project welcomes images and stories as long as there is an Indian context.

Image contributed to the Indian Memory Project by Nate Rabe, Melbourne, Australia: “My friends, Jeff Rumph, Martyn Nicholls, and I (centre), an unknown boy and my father, Rudolph Rabe (right), Dehradun, Uttar Pradesh (now Uttaranchal), June 1975.” Used with permission.

GV: What is your favourite photograph and story currently on the site?

AY: The latest post is usually my favorite post until another comes along! Each post is a favourite because it is another clue in our attempt to trace India's history.

The ease with which people reveal family secrets or previously unmentioned or suppressed narratives is also very interesting to me. How much people are prepared to say reflects how our society is evolving.

This video introduces the Indian Memory Project:

1 comment