*This interview is reproduced the way it was done, in “Spanglish,” a mix of Spanish and English. The Spanish portions have been translated into English for this article.

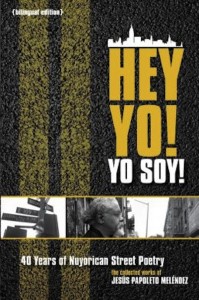

Studying the Nuyorican movement is essential, as is well known to those who search for freedom through writing [Nuyorican is the name given to Puerto Ricans from/in New York]. For this very reason we celebrate the extraordinary career of poet Jesús “Papoleto” Meléndez, one of the fathers of the Nuyorican literary movement, who just released the poetic collection entitled Hey Yo!, Yo Soy! 40 Years of Nuyorican Street Poetry.

Thanks to the work of 2Leaf Press and translations by Adam Wier, Carolina Fung Feng and Marjorie González, Meléndez's first three books of poems –Casting Long Shadows (1970), Have You Seen Liberation (1971), and Street Poetry & Other Poems (1972)– are now available in English and Spanish.

This book will travel from the Spanish Harlem “El Barrio”, New York, to Latin America, Africa, Europe, and the entire world to “create a more free world through the rebellion that brews even in the smallest acts,” explains Myrna Nieves, Puerto Rican writer and editor based in New York.

Below we share portions of a conversation with Jesús “Papoleto” Meléndez where we can appreciate not only his linguistic freedom, but also his poetic, aesthetic and even spiritual vision in the most human sense of the word.

Global Voices (GV): Let's talk about your poetry.

Jesús Papoleto Meléndez (JPM): Yo la llamo still life poetry porque son como las pinturas still life. Mis poemas son así…Es como si la vida se quedará quieta para el momento del poema.

Jesús Papoleto Meléndez (JPM): I call it still life poetry because they are like still life paintings. My poems are like that…It is as if life will remain quiet at the moment of the poem.

GV: What do you call the poetic/visual technique that you have developed through out the years?

JPM: Cascadance.

GV: In one of the first poems in the book you talk about sitting in front of an open window.

JPM: Ese es el primer poema que yo escribí en mi vida.

JPM: That is the first poem that I wrote in my life.

GV: How old were you?

JPM: Let me see we had moved to the Bronx when I wrote that. I was about 15.

GV: Did you print and bind your poems at the printer in the school where you studied?

JPM: By the time I graduated from Morris High Shcool, I had printed the three books. I remember it was a crazy summer. Escribí los tres libros, uno detrás del otro. I was very productive, and then all hell broke loose; and I stopped being productive because life got in the way, that is what I say…

JPM: By the time I graduated from Morris High Shcool, I had printed the three books. I remember it was a crazy summer. I wrote the three books, one after the other. I was very productive, and then all hell broke loose; and I stopped being productive because life got in the way, that is what I say…

GV: Do you hear a voice when you write?

JPM: Yeah, I do hear a voice, and I hear the placement. It’s not play time…

Yo voy entonando los poemas mientras van saliendo de mí…pero el poema está controlando todo. Yo lo estoy tratando de oir. Yo no estoy creando la voz del poema, estoy dejando que el poema haga eso.

La poesía entra en tí porque está buscando voz. Vuela por el cosmos buscándola. Tiene propósito, pero no tiene voz.

JPM: Yeah, I do hear a voice, and I hear the placement. It's not play time…

I set the tone for the poems as they come out of me…but the poem is controlling everything. I am trying to hear it. I am not creating the voice of the poem, I am letting the poem do that.

Poetry enters you because it is looking for a voice. It flies through the cosmos looking for it. It has a purpose, but it does not have a voice.

GV: So poetry is closely related to your spirituality.

JPM: When people make statements like: “oh, it's easy to write poetry,” [I say] it might be easy to write poetry for you right now, but if you keep writing poetry is going to get harder. The reason why it's easy for you is because you haven’t dug deep into that hole. You know, the more you know the harder it is to express it.

I think that we are spiritual beings having a human experience. You see, so we came here specifically to have a human experience. Now, where we came from? We came from whatever the hell the cosmos is about; we are all part of that…Now, we have two mandates. There are two rules to our existence. One is live as long as you can. You see, stay alive, don’t get hurt. Why? So that you can meet the mission. The mission is to gather as much information as possible…

GV: How do you associate these ideas into our daily life?

JPM: You have to think outside of the box, and you are the box. The reason why we have a body is so that we can interact, otherwise we be going right through each other like we normally do…We need to ground our spirit so it can interact…

GV: The poems that you wrote in the 60s and 70s continue to be relevant. Sometimes one wonders how much the situation has changed, particularly in New York.

JPM: En esa época nosotros no teníamos mucho apoyo. Básicamente acabábamos de llegar, so we had to defend ourselves and we had to create. There was no favoritism, a ellos [the system] no le gustaba ciertos latinos más que otros. They hated everybody.

The only way to survive is by [creating] community. So when we wrote and created art we did it to preserve our culture, enrich ourselves, fortify ourselves to go against the system.

Nowadays, people don’t have that struggle. We have the benefits of everything that happened…They are writing for themselves, but they say they are writing for the people.

JPM: At that time we did not have much support. Basically we had just arrived, so we had to defend ourselves and we had to create. There was no favoritism, they [the system] did not like certain Latinos more than others. They hated everybody.

The only way to survive is by [creating] community. So when we wrote and created art we did it to preserve our culture, enrich ourselves, strengthen ourselves to go against the system.

Nowadays, people don’t have that struggle. We have the benefits of everything that happened…They are writing for themselves, but they say they are writing for the people.

GV: Although you are one of the founders of the Nuyorican movement, you see poetry beyond categories, labels.

JPM: La poesía siempre es más de lo que se supone que sea…Poetry had to be an initial form of communication because it is brief and concise. But now in modern society it becomes the bastard of literature. It becomes this stepping stone.

JPM: Poetry is always more than what it is thought to be…Poetry had to be an initial form of communication because it is brief and concise. But now in modern society it becomes the bastard of literature. It becomes this stepping stone.

GV: Circling back to the anthology, Hey Yo!, Yo Soy! 40 Years of Nuyorican Street Poetry, what was its translation process like?

JPM: Fue challenging y exciting. Cuando nosotros planificamos [la publicación de] este libro no pensábamos traducirlo al español. Inicialmente, the publisher Gabrielle David, solo pensó en publicar mi primer libro. She deserves a lot of credit, not only for the vision but for her drive and her knowledge.

JPM: It was challenging and exciting. When we planned [the publication of] this book we did not think to translate it to Spanish. Initially, the publisher Gabrielle David, only thought to publish my first book. She deserves a lot of credit, not only for the vision but for her drive and her knowledge.

We invite you to watch Jesús “Papoleto” Meléndez in the following video, and call 1-630-4-A-Rhyme (“Dial-A-Rhyme”), where you can listen to him read his poems.

1 comment