Yesterday, on December 3, The New Times published a retrospective [ru] on last winter's mass protests, highlighting how the Internet played a vital role in mobilizing thousands of people in a city that, until then, could only produce a few hundred demonstrators at a time. The middle class, the youth, and the technophiles of Moscow had awakened and the possibilities seemed endless.

Then came the “schism,” what The New Times describes as a night the opposition's leaders “would prefer to forget.” In what has provoked much discussion in the RuNet today, The New Times piece includes revelations from journalist-activist Sergei Parkhomenko [ru], who now recalls new details about a closed-door meeting with Moscow city officials late on December 8 that resulted in the transfer of the December 10 mass rally from Revolution Square (where it was originally planned, just outside the Kremlin) to the less central Bolotnaia Square. As it turns out, Alexey Gromov — then deputy chief of staff under President Medvedev — had attended the meeting, dropping by to confirm its resolution and partake in a celebratory round of whisky (courtesy of Ekho Moskvy chief editor Alexey Venediktov, who was also present).

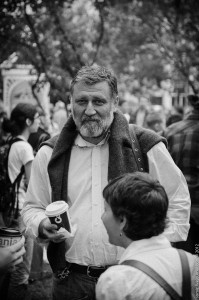

Sergei Parkhomenko, attending the “Occupy Abai” protest, 11 May 2012, photo by Evgeniy Isaev, CC 2.0.

What's so scandalous about Gromov's appearance at this meeting? Many, Parkhomenko included, would reject the question, arguing that his attendance changes nothing. Parkhomenko explains:

Громов сел за стол и вел какой-то не относящийся к делу разговор. Мне кажется, он хотел убедиться, что все происходит ровно так, как рассказывает ему Горбенко

Gromov sat at the table and carried on some conversation that didn't relate to ours. It seems to me that he wanted to make sure that everything was happening just as Gorbenko had described it to him.

Alexander Gorbenko, Moscow's deputy mayor, was ostensibly the one who hosted the meeting, which also included city officials Vladimir Kolokoltsev (then head of Moscow internal affairs), Vasily Oleinik (deputy head of Moscow regional security), and Gulnara Penkova (the mayor's press secretary), not to mention Parkhomenko, Venediktov, and oppositionists Vladimir Ryzhkov and Gennady Gudkov (though the latter individual apparently “doesn't remember” this). In other words, this was a gathering of Moscow's administrators and the protest movement's self-appointed leaders. While the secrecy of the consultations upset many protesters at the time (indeed, The New Times credits it with diminishing the movement's popularity among young people), it was still formally true at least that the negotiations were with the city and not the Kremlin. This, it seems, imbued the talks with a certain legitimacy, even if that impression was only sustainable from an admittedly naive perspective.

Journalist and blogger Oleg Kashin wrote on Parkhomenko's Facebook page earlier today, accusing [ru] him of “concealing” the fact that Gromov participated in the December 2011 negotiations, asking him why he said nothing [ru] of it at the time. Parkhomenko defended himself [ru] within minutes:

[…] а что именно меняет в этой истории появление (физическое) Громова? Вас удивляет, что он дергал за ниточки Горбенку и прочих “мэрских”? Вы об этом сейчас от меня узнали? Физически в переговорах он участия не принимал – во всяком случае, я никогда в таких переговорах не участвовал. Что Горбенко каждые пять минут выбегал из комнаты с кем-то советоваться по телефону – всегда было важной частью всех разговоров про эти дни.

[…] and what exactly changes in this story with the (physical) appearance of Gromov? Does it surprise you that he was pulling the strings of Gorbenko and all the other “mayor's people”? You just learned about this from me? Physically he didn't participate in the talks, or I at any rate never participated in such negotations. That Gorbenko would run out of the room every five minutes to consult with someone over the telephone was always an important part of all these conversations.

After a scolding [ru] from Kommersant's Arina Borodina, Kashin ceased his questions [ru] to Parkhomenko, convinced that arguing about Gromov's role would only play into the Kremlin's hands.

Other Russian Internet users, however, were not so quick to forgive, attacking Venediktov and others for colluding with the federal government.

Roman Fedoseev (@morkvo) tweeted:

охуительная история, как Венедиктов и Громов из АП выпили вискаря и перенесли митинг с Революции на Болотную. сука-сука

what a f*cking story, how Venediktov and Gromov from the [Presidential Administration] drank whiskey and moved the rally from Revolution [Square] to Bolotnaia. sonofabitch

Twitter user @sssmirnov wrote sarcastically:

а давайте в следующий КС выберем Горбенко и Громова, Венедиктов же объективный журналист и не будет участвовать

how about for the next [Coordinating Council], we elect Gorbenko and Gromov? Venediktov's too objective a journalist and wouldn't run

Arkady Babchenko, a former candidate for the Coordinating Council and a deeply polemical figure within the opposition, reposted the story from The New Times, writing:

Как, кто, с кем, в каких кабинетах, с какими чиновниками и какими словами договаривался о сливе революции под вискарь Венедиктова в ночь на 9 декабря. По ролям. Мастрид.

[It's about] how, who, with whom, in what offices, with which officials, and with what words it was agreed to drown the revolution in Venediktov's whiskey in the early morning hours of December 9. Role by role. A must-read.

Much about the negative reactions to Parkhomenko's latest disclosure might be dismissed as emotional. Indeed, it appears almost common among netizens to experience a pang of disgust at learning that Venediktov marked this cloak-and-dagger event with a celebratory bottle of booze. On the other hand, the informality of the protest movement's leadership has changed significantly in the last few months, thanks to a Coordinating Council that at least superficially offers the opposition's leaders a mandate to lead. In today's situation, any dealings with Gromov or the Kremlin would ideally occur with protesters’ duly elected representatives.

The question remaining, however, is whether or not the Putin Administration has any lingering interest in negotiating with a protest movement that, after a year's time, is on the decline.

2 comments