This post is part of our special coverage Russia's Protest Movement.

Anyone following the Russian protest movement cannot help but notice the degree to which many Russian journalists are involved with the opposition. Not only do they actively attend rallies — they also eat at the same cafes, drink at the same bars, and go to the same clubs as the movement's leaders. In the age of Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, such interpersonal relationships are clearly visible to outside observers.

Although this is questionable behavior by Western standards (National Public Radio, for example, actually prohibits staff from participating in protests, even outside of work), it has failed to attract any attention in Russia, until last Monday.

On September 17, Ekho Moskvy radio host Alexander Plushev tweeted the following [ru]:

Я считаю, что журналисты, баллотирующиеся в КС оппозиции — это безобразие. Либо ты в оппозиции, либо журналист.

I believe that journalists running for the opposition's Coordinating Council is a travesty. Either you’re in the opposition, or you’re a journalist.

He then elaborated [ru]:

Хочешь в политику — на время/навсегда перестань называть себя журналистом. Хочешь оставаться журналистом — и думать забудь про всякие КСы

[If] you want into politics — temporarily/permanently stop calling yourself a journalist. [If] you want to stay a journalist –- forget about Coordination Councils.

Plushev was referring to the fact that quite a few journalists (according to him, as many as twenty) are participating in the opposition's coming Coordinating Council elections [ru]. Writing on his personal blog [ru], he expanded on the idea, describing the phenomenon as ethically reprehensible, and citing the Moscow Charter of Journalists [ru], a 1994 document that, among other points, tries to draw a clear line between journalism and politics (a line that was blurry during the Soviet Union).

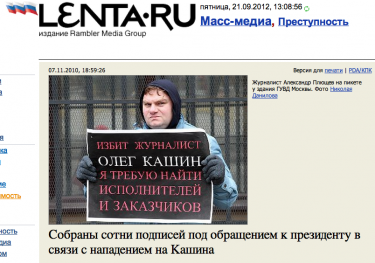

Alexander Plushev picketing, ironically in light of today's dispute (on several levels), in support of Oleg Kashin, after his brutal beating. Sign reads, “Journalist Oleg Kashin has been beaten, and I demand that those who committed and ordered this crime be found.” 7 November 2010. Screenshot from Lenta.ru.

The Council will clearly be a highly political organization, tasked with anything from ranking opposition leaders to being a “shadow government” and coordinating street protests [ru]. (As a nascent institution, the jury is still out on what it will do, exactly.) Though journalists joining the Council would seem to represent an obvious violation of the 1994 Charter's principles, many have attacked Plushev for arguing just that. Ironically, one of his most vocal critics is Sergey Parkhomenko, an original signatory of the 1994 Charter. Parkhomenko is himself running for a position on the CC and wrote a lengthy blog post [ru] in response to Plushev, where he oscillated between claiming (1) that membership in the Coordinating Council is not a “position,” and (2) that Russian journalism is ethically bankrupt anyway.

Although he calls himself a journalist [ru], Parkhomenko has a pass to seek political involvement. According to his boss at Ekho Moskvy and fellow Charter-signatory Alexey Venidiktov, Parkhomenko is not a staff journalist, but rather an op-ed columnist. This makes his participation in a political organization “not frightening,” [ru] according to Leonid Bershidskii, former editor of Slon.ru and current editor of Forbes.ua.

Venediktov later tweeted [ru] in support of Plushev, expressing his “solidarity.” Another old-school journalist, Sergey Korzun, agreed, drawing a distinction between columnists, publicists, and journalists, writing [ru]:

Когда в процесс политического лоббизма вовлечены штатные журналисты, издание теряет свой статус 4-й власти.

When staff journalists become involved in political lobbyism, the publication loses its status as a member of the Fourth Estate.

Journalist Oleg Kashin responded with an article [ru] on Slon.ru, where he dismissed Ekho’s impartiality internal policies as quaint and “last-century corporate rules.” Proud that these rules do not apply to his own work for Kommersant, Kashin is of the opinion that a journalist can’t avoid bias. And if that is the case, why pretend to be objective by staying out of political organizations?

Oleg Kashin (center) attending protests at Chistye Prudy in Moscow, 10 May 2012, photo by Evgeniy Isaev, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Those who disagree with Plushev -– among others, former Kommersant chief editor Demian Kutdriavtsev [ru], journalist Kirill Martynov [ru], and political activist Oleg Kozyrev [ru] –- all parrot Kashin's argument. It is impossible for a journalist to be truly objective, therefore political participation subtracts nothing from the quality of their work — indeed, it can even enhance it, since activism clearly exposes the bias of the journalist. There is a logical disconnect here: Plushev does not argue against having opinions, he argues against subjecting those opinions to the influence of participation in the process being covered.

Oddly, Kashin and Martynov believe that the world, including the United States, is full of “party” newspapers and “left and right publications” for which political bias is a badge of honor. Assuming that this is the case (a dubious proposition for mainstream American journalism, which is often criticized for having gone too far in the other direction with its “teaching the controversy” style), it does not follow that staff of these organizations is actively political. Even most FOX News anchors, for all of their opinionated support for the Republicans, would probably not participate in the kind of official party structure that the Coordinating Council is in essence.

Of course, there are other cases made against Plushev. Some ask [ru], “But what will journalists eat, if they quit their jobs to become politicians?” The answer is unclear. Others, like Kudriavtsev, argue that it is essential that journalists be a part of the protest movement because they represent society. Arguments like this have led Maksim Kurnikov, a regional editor at Ekho Moskvy, to tweet [ru]:

@plushev мне кажется, или большинство отвечающих про журналистов и КС, не опровергают ваши тезисы, а переводят разговор в “кто, если не мы?”

@plushev is it just me, or is the majority of people responding to journalists and the CC not arguing with your thesis, but rather changing the conversation to “if not us, then who?”

Another interesting point, made by the ostensibly pro-Kremlin publicist Dmitry Olshansky in his Facebook [ru], is that Russia has a rich turn-of-the-century tradition of journalist-politicians. In his list, he includes Lenin, Trotsky, Kropotkin, Plekhanov, and many others. Some of Olshansky’s commenters point out [ru] that, although these people did write and even published newspapers:

Деятельность тех людей в то время в тех СМИ больше всего походит на нынешнее блогерство или ведение колонок. Блогеры – это не журналисты

The activity of those people, at that time, and in those mass media, is more akin to modern blogging and writing op-eds. Bloggers aren't journalists.

This is a comforting thought. The Internet would have been a powerful tool in the hands of Lenin, Trotsky, or Purishkevich, undoubtedly putting the current propaganda flame wars to shame.

This post is part of our special coverage Russia's Protest Movement.