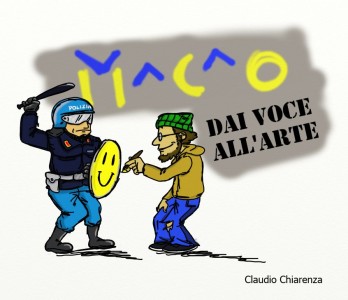

In the early hours of the morning on May 22, 2012 police and army entered Palazzo Citterio in Milan, Italy ending for the second time an occupation by about 60 artists and precarious workers gathered under a collective known as “Macao”.

[All links point to Italian sources except where otherwise stated].

The group of architects, visual artists, students, communication and education workers had occupied the 16th century building on May 19, after their eviction from the Galfa Tower, where they had stayed for ten days [en]. The eviction order for Palazzo Citterio, however, was issued immediately. The eviction was non-violent and found no resistance on the part of the occupiers.

On May 5, the collective began occupying the Galfa Tower, a 33-floor skyscraper in the heart of Milan. Owned by the financial services company Fondiaria SAI, the tower has been empty for the past 15 years. The collective re-named it Macao, an acronym whose meaning, they say, is open to interpretation, reflecting the openness of the project itself.

On the first day of occupation, a banner was unfolded from one of the top floors that read: “We could even imagine to fly.” The tower was cleared by police on May 15 and ten of the participants were arrested. The collective then camped out in front of the building for four days, until they decided to proceed with the occupation of Palazzo Citterio.

Macao's aim is to ‘liberate’ space for the arts in a city where spaces for the young and for creativity are scarce. During the ten days of occupation, some of the skyscrapers’ floors were cleaned up and made accessible for meetings, assemblies, workshops and seminars. As summed up by one of their tweets:

@MacaoTwit: #MACAO non intende essere un altro centro per le arti, ma un nuovo centro per le arti : #tuttiSUmacao

The Milan occupation is only the latest in a series that blossomed throughout Italy over the past year, including at the Coppola Theatre in Catania, the Garibaldi Theatre in Palermo (both in Sicily), the Knowledge and Creativity Nursery in Naples, the Sale Docks in Venice, the Valle Theatre and Cinema Palazzo in Rome. Together, these form part of the network Lavoratori dell’Arte (Art Workers).

There are two main reasons behind the occupations. On the one hand, the shutdown of public bodies such as the ETI (Italian Theatre Association) and cultural spaces, which followed the cuts to public sector funding for the cultural industries implemented by the Berlusconi government since 2010. On the other hand, the job insecurity blighting the culture and communications sector, whose workers (most of whom are freelancers or employed on short-term contracts) tend to lack traditional trade union representation and access to welfare.

It is in this context that the movement of the Art Workers is born. As they explain on their website [en]:

Art Workers assert that Art and Culture should obtain the status of common good. The common good is not an abstract concept but a new living form of democracy that aims to overcome the dichotomy between public and private sectors.

For this reason, we, as Art Workers, must explain the precarious conditions in which we operate with clarity. It is very important to recognize the dynamics, the ambivalence, the extent of precariousness, especially where the term seems to be devalued. Moreover, we can only field effective countermeasures by starting from a lucid diagnosis, especially when the economic crisis has implemented the severity of our condition.

Let’s say that artistic languages are a political fact and that insecurity obstructs experimentation, ambition, intelligence, radicalism and art’s global reach.

Macao's press release [en] similarly states:

We are the multitude of workers of the creative industries that too often has to submit to humiliating conditions to access income, with no protection and no coverage in terms of welfare and not even being considered as proper interlocutors for the current labor reform, all focused on the instrumental debate over the article 18. We were born precarious, we are the pulse of the future economy, and we will not continue to accommodate exploitation mechanisms and loss redistribution.

The Art Workers define themselves as brains in struggle, not in drain [en]. Similar experiments took place in Portugal, where a self-managed community Es.col.a was evicted in April [en]; in Spain with Hotel Madrid [es]; and in the United Kingdom with the occupation by the activists of Occupy London of an empty building in the City of London, owned by investment bank UBS and renamed Bank of Ideas [en].

Despite the evictions, the projects have tended to gather a degree of public support, which was formerly unthinkable seeing as occupying public or private buildings remains illegal. In Italy, a tradition of occupying social centres [en] dates back to the struggles of the 1970s, but these occupations have reached record levels of support, including from high-profile figures like Nobel-prize winning satirist Dario Fo [en], and even some local authority officials.

Furthermore, Macao's Facebook page has already garnered over 30,000 ‘likes’, whilst the hashtags #macao and #iostoconmacao were trending on Italian Twitter on the day of their eviction from the Tower – with about 300 people peacefully confronting police officers. Well-known journalist Luca de Biase opined on his blog:

Lo sgombero del Macao avviene in una città che non ha protetto lo spazio pubblico – fisico e culturale – dall’invasione delle recinzioni e delle privatizzazioni – fisiche e culturali. E che quindi oggi si interroga su uno spazio privato che alcuni interpreti dell’apertura pubblica volevano riconquistare.

On the other hand, there are those who criticise the project for its frivolity at a time of crisis, like the authors of the blog Frankestanislao:

Certo i fighetti radical chic che indossano l’abito da indignati della domenica mi fanno ridere, ci sono altre priorità per cui scaldarsi!..

For others, such as for some of those who have left Italy searching for better opportunities, Macao becomes the symbol of hopeful change; as Francesco Cingolani, one of the many young professionals who joined Italy's “brain drain”, writes on his blog Immaginoteca:

Tutto questo mi fa venire voglia di tornarmene in Italia per fare una fuga di cervelli al contrario.

The local council administration has offered an alternative space to be used as an art centre open to all, but Macao has refused the offer. The debate is still open, and at the time of writing the collective continued to hold public assemblies. To sign a petition to save Macao, send an e-mail ‘proteggiamomacao [at] gmail [dot] com’.