[All links lead to sites in French unless otherwise stated.]

The use of satirical language and cartoons in the media is relatively new in most African countries, and began with the print publication of small cartoon strips featuring caricatures depicting a particular part of the population for comic effect. Often, satirical newspapers are a reflection of the state of political affairs in their countries, where politicians never seem to shy away from shameless actions and where dishonesty is the rule rather than the exception.

Satirical language

In an analysis for the site cairn.info, Yacouba Konaté describes the mixture of Molière's French with the local dialects in Côte d’Ivoire where the direct translation from one to the other gives expressions and phrases that are incomprehensible outside their geographical context:

Le français populaire ivoirien dit « français de Moussa », « de Dago » ou « de Zézé » (héros de bandes dessinées dans l’hebdomadaire Ivoire Dimanche), accélère son déploiement durant les années 1970, celles de la croissance ivoirienne qui supporta l’appellation merveilleuse de « miracle ivoirien ». Sa promotion bénéficia de l’appui de la télévision où, pendant des années, le dimanche ouvrit de larges plages horaires à Toto et Dago.

In Gabon, a similar method of speech has gained acclaim by becoming a way of exposing corruption and social criticism. A selection of words taken from Raponda-Walker's book on the language is presented by Falila Gbadamassi on the website afrik.com:

Le “bongo CFA”, désigne la monnaie gabonaise qui était autrefois à l’effigie du défunt président Omar Bongo. Le terme se rapporte aussi à l’argent distribué pendant les déplacements du Président ou les campagnes électorales. …. [“mange-mille”] est un « jeu de mots construit sur mange-mil (nom d’oiseau) et désignant le policier ou le gendarme en raison des billets de 1000 francs (FCA, ndlr) qu’ils réclament souvent aux usagers de la route. Et des “Chine en deuil” ? Ce sont des « chaussures noires en tissu souple de fabrication chinoise ou asiatique introduites au Gabon après la mort de Mao Ze Dong », …. Un “dos-mouillé”, lui, est un immigré clandestin originaire d’Afrique de l’Ouest qui arrive au Gabon par la mer.

Election results confirmed by Ali Bongo: a TOTAL victory! I would like to thank my sponsor… A caricature of Bongo by Hub via Agora Vox, used with permission

In both Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire this type of French is used in everyday life in the same way as all other languages, without any derogatory meaning or humourous intent, but when it appears in publications or on TV it serves for social and political critique, with the singular ability to make an otherwise unfunny drawing make people laugh. The textual content is paramount.

Cartoon emergence

Cartoon drawings, or comics, were developed later only, as and when authoritarian regimes relaxed their grip on freedom of expression. In an article published on waccglobal.org, Gado wrote a retrospective history of cartoons [en] in African countries:

With the introduction of multi-party politics in most African countries during the 1990s, cartooning emerged as a growing profession. This does not mean that it was not around before then. In the 1960s there were pioneers like Gregory (Tanzania) with his popular Chakibanga cartoon and the Juha Kalulu strip by Edward Gitau, the oldest living cartoonist in East and Central Africa.

Political changes brought greater freedom of expression as well as of the press. This has injected new life into newspapers, magazines and the publishing industry generally.

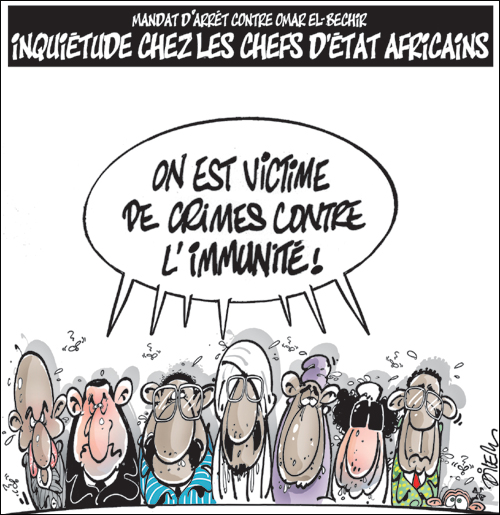

Arrest warrant for Omar El-Bechir. Disquiet among African heads of state. We are victims of crimes against immunity! A caricature of the African heads of state by Dilem via Zoom Algérie (used with permission)

To mark the 2011 International Festival of Cartoons and Illustration, which took place in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Damien Glez's article published on africandiplomacy.com entitled “Newspaper Cartoonist: a Profession under Pressure(s)” discusses the risks and difficulties involved in being a satirical cartoonist:

Moins assassinés, les dessinateurs ne sont pas totalement immunisés. Au Cameroun, le caricaturiste-vedette Nyemb Popoli a eu maintes fois maille à partir avec le régime de Paul Biya. A la fin des années 80, dans le Bénin du «marxisme-béninisme», le dessinateur Hector Sonon voyait ses dessins systématiquement passés à la moulinette du comité de censure du ministère de l'Intérieur. Le Sud-Africain Jonathan Shapiro, alias Zapiro, fut détenu par les autorités en 1988. Non loin, au Zimbabwe, le dessinateur Tony Namate joue au chat et à la souris avec les autorités. Au Nigeria, autre pays anglophone, les caricaturistes – en premier lieu le pionnier Akinola Lasekan – ont souffert longtemps des dictatures militaires…

Participants in the festival, organised by Cartooning for Peace / Dessins pour la paix, included Karlos from the Ivory Coast, and Timpous, Gringo, Joël Salo and Kab's from Burkina Faso.

In South Africa, Shapiro, of the apartheid era, was sent to prison for angering racist authorities with his critiques, and now his stands against the African National Congress's grip on the politics of his country are costing him dearly. Melanie Peters describes a critical cartoon [en] on iol.co.za condemning President Zuma's bill from last year, and reports on feedback from netizens:

While the cartoon depicts a man titled “Govt” with his trousers unzipped facing a screaming woman being held down by a man labelled “ANC”, the first is clearly Zuma, complete with showerhead, and the second Gwede Mantashe, the ANC’s secretary-general. Next to them on the floor, her dress torn and a discarded pair of scales beside her, is an apparent rape victim, shouting “Fight, sister, fight!”

Some comments posted on the site contain personal and racist abuse, but support can also be found. Siobhan wrote [en]:

Go, Zap! Exactly depicts what is happening with the ‘secrecy’ bill! It's being done to the Constitution, to Democracy and to each South African- most of whom are so used to being screwed by the ANC they don't even know it's happened…

New talent

Until recently, the cartoonists had no training. But changes are being made. According to Alimou Sow, Oscar, the creator of Le Lynx, has trained a number of junior colleagues in Guinea. However, it is probably in Madagascar that the first generation cartoonists have best prepared their successors, with production diverse and thriving equally in both national languages and French. According to the provisional list proposed by wikipedia.org, the number of Malagasy artists is several times higher than that of all the other African countries combined.

The publication of satirical newspapers in several countries has allowed satire to exist and thrive amid a great number of difficulties: in Senegal, Le Cafard libéré; in Burkina Faso, the Journal du Jeudi and the latest l'Etaloon; in Benin, the Canard du Golfe; in Guinea, Le Lynx; in Mali, Le Canard déchaîné; in Madagascar, the Ngah; etc.

Christophe Cassiau-Haurie tells us in an article on africultures.com entitled “La caricature à Maurice, 170 ans d'histoire” (Cartoons in Mauritius: 170 years of history) that:

La toute première caricature référencée remonte à l'année 1841, dans le journal Le bengali.

Festivals and other events are also on the increase both regionally and throughout Africa. The article already cited by Damien Glez lists these:

«BD'Farafina» à Bamako, «Cocobulles» à Grand Bassam, «Fescary» à Yaoundé ou «Karika'Fête» à Kinshasa.

Information and communications technology is another tool that is beginning to take its place among the means of expression for African comedians: zapiro.com, bing.com, africartoons.com, 2424actu.info and gbich.com, for example.

On an international level, Africans are increasingly present. For example, they participate in the Cartooning for Peace / Dessins pour la paix‘s activities, started in 2006 by the French cartoonist Plantu together with Kofi Annan, then the Secretary-General of the UN, with a two-day conference uniting the 12 most famous illustrators in the world to develop ways to “unlearn intolerance”.

3 comments