In Fortaleza [1], the fifth largest city in Brazil, the recent start of construction on an aquarium has prompted discussions over public resources, state government priorities and the city's future, as well as some creative forms of protest.

Estimated to cost 250 million Brazilian reais (approximately 136 million US dollars), the project promises to become the world's third biggest aquarium. On January 30, 2012, the State of Ceará tourism secretary shared a preview of what Acquario Ceará will offer to the public once concluded:

As promising as the project might seem, its high cost has been subject to criticism [2], mainly by citizens who believe the budget should be deployed in the areas of education, security, and health, in which the state of Ceará features several deficiencies.

Harboring similar doubts about the project, artist Enrico Rocha published a photo [3] [pt] on Facebook on February 5, 2012 of the planned construction site, ready for construction, and subsequently triggered a debate which extended to 150 comments.

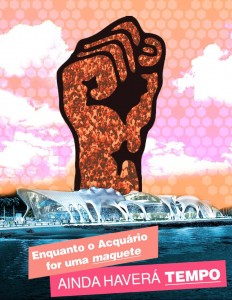

[4]

[4]"As long as the Acquario remains a model, there will be time". Illustration by Yuri Leonardo, used with permission.

Ten days after Enrico Rocha's photograph, the Facebook page for the movement opposing the aquarium, Quem dera ser um peixe [5] (I wish I were a fish) [pt], was created. The group is named in reference to the song Borbulhas de amor [6] [pt], by Ceará-born singer and composer Fagner, whose verses “Quem dera ser um peixe/Para em teu límpido/Aquário mergulhar” (I wish I were a fish/To dive in your/Limpid aquarium) go hand-in-hand with the movement's criticisms.

The blog page Why We Question It [7] [pt] features reasons to oppose the aquarium, specifically the lack of transparency surrounding it.

Among the objections, there is no evidence that the companies Imagic [8] [pt], which designed the aquarium, and the North American ICM Reynolds [9], which is building it, were hired through public bidding. Critics question the irregular building permit granted to the project, given that “mandatory archaeological reports, which must be analyzed and approved by the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage (Iphan)” had not been conducted.

Furthermore, the bill of such enterprise will go “beyond the debt, with a monthly cost estimated at 1,5 million Brazilian reais (815,000 US dollars)”, and clings to a business plan that remains unknown:

Não foi apresentado um plano de negócios que mostre, detalhadamente, como iremos saldar a dívida que teremos com o banco norte-americano Ex Im Bank of United States, com quem o Governo do Estado está negociando empréstimo de aproximadamente US$ 105 milhões. O restante dos gastos sairia diretamente dos cofres públicos no valor de US$ 45 milhões.

Carnival parade and weekly meetings

On February 22, revelers during Carnival who shared a critical view toward the project came together in a small parade called Unidos Contra o Acquario (United Against the Aquarium), which snaked throughout the streets of the Benfica neighborhood alongside the traditional parade, known as Sanatório Geral. Revelers dressed up as fish and walked under a vast blue cloth mimicking the sea.

[10]

[10]Bloco Unidos do Acquário (Aquarium United Block). Photo by Quem dera ser um peixe, used with permission.

In previous years, the Sanatório Geral parade had already played a carnival march called Fortaleza Aquática [11] (Aquatic Fortaleza) [pt], which mocks the project and mentions previous controversies regarding Governor Cid Gomes’ administration.

Another kind of mobilization taking place are meetings known as Inundação (Flooding), shared under the hashtags #OcupePI (Ocuppy Praia de Iracema) and #DesocupeAcquario [12] (Desert Acquario) and organized and attended on Saturdays by supporters of the Quem dera ser um peixe movement, in the Praia de Iracema neighborhood, which is set to host the aquarium. The first meeting occured on March 10, and gathered citizens opposed to the project as well as residents of Poço da Draga, a century-old community that will face forced evictions to open space for a parking lot for the aquarium's visitors.

The State government's reaction followed shortly after the first meeting. The then recently created institutional Twitter profile @acquario_ceara [14] responded [15] [pt] to the controversy not with facts, but with accusations instead:

@acquario_ceara [14]: Quem está contra o #AcquarioCeara trabalha contra o desenvolvimento do Ceará. Parece que são pessoas a serviço de outros estados.

Also on Twitter, student Débora Vaz linked to [16] [pt] the video [17] shared by the historian Andréa Saraiva on the blog Chafurdo Mental [18] [pt], denouncing the start of the construction before such a permit was granted. She said:

@deboravaz [16]: Enquanto isso, aqui em Fortaleza, a estúpida obra do Acquário começa sem alvará, além de ter sido contestada pelo Iphan http://youtu.be/PUtNBHg27FQ [19]

Lack of transparency

The Quem dera ser um peixe movement published [20] [pt] documents denouncing irregularities in the project's bidding on April 11:

Dentre os nossos pedidos está o de cancelar imediatamente o processo de contratos já efetuados. Veremos que na surdina o governo tem contratado e licitado ao arrepio da lei e que já está superando o numero milionário de R$ 250 milhoes iniciais.

Veremos também que já foi pago R$ 876 mil reais que ninguém sabe pra quem e nem pra quê, pois o governo não publicou os termos como seria de sua obrigação.

Among our requests is the immediate revocation of contracts already in effect. We will see that on the sly the government has authorized and hired disregarding the law, so far exceeding the original millionaire sum of 250 million Brazilian reais.

We will see that 876,000 reais have been deployed to pay no one knows who and nobody knows the reason, since the government hasn't published the terms of the transaction, as it was supposed to.

Facebook user Alexandre Ruoso shared his comments on the news, writing [21] [pt]:

#AquarioIlegal #GovernoFazdeconta

Se isso acontece em obras como esta, que tem toda a visibilidade, imagina nas obras menos importantes.

If such practice occurs in projects like this, which is under the spotlight, I wonder what happens in less important projects.

Considering the government's lack of transparency in mobilizing 250 million reais to build the Acquario Ceará, many have questioned the arguments used by Governor Cid Gomes during recent strikes [23] by military police officers and teachers, occasions in which he refused to comply with workers’ demands.

Protests have taken place in other cities of Ceará as well, not only Fortaleza, as Professor Tiago Coutinho reported [24] [pt] on his Facebook page on April 2:

Neste momento estudantes da Urca ocupam as ruas do Crato e cantam “é ou não é piada de salão, tem dinheiro pro aquário mas não tem pra educação?”.

Andréa Saraiva questioned [25] [pt] the model of tourism reinforced by the Acquario on her blog, arguing that it ignores cheaper and more interesting alternatives for the communities:

O turismo é uma atividade econômica como outra qualquer, portanto ela não é neutra. Aqui no Ceará várias comunidades sofrem pelo turismo predatório, grande aliado da especulação imobiliária, das empreiteiras e do turismo sexual que vem sendo aplicado em sucessivos governos que investem em modelos que só favorecem a industria do turismo. A concepção Tasso-Cidista [referência ao ex-governador Tasso e o governador Cid] de desenvolvimento no Ceará baseado na industrialização se mostrou fracassada e só melhorou a vida de grandes empresários, o número de miseráveis só aumentou. Há outros modelos de turismo exitosos no mundo e até aqui no Ceará que é referência internacional em turismo comunitário. Mas não há investimento porque estes não financiam campanha, esse tipo de turismo não é ‘montado no cimento’.

The project's sustainability has sparked questions [26] [pt] as well, mainly after reports of cultural centers in town being in disrepair, such as the Centro Dragão do Mar de Arte e Cultura [27].

Local mainstream media coverage has proven itself to be ambiguous, but an article [28] [pt] written by journalist Adísia Sá highlighted the need of a public consultation on the project. She said:

Volto a insistir: a população tem o direito de ser não só informada como consultada. E não venham me dizer que deputados e vereadores sabem de tudo e que eles, sim, são a opinião pública. Todos foram eleitos com os nossos votos, sim, mas não lhes foi dada carta de alforria para falar, agir e decidir por nós – em qualquer assunto. Há limite na representação popular. E, pelo visto, isto não está sendo considerado.