In the beginning of this year, the city of Lavras, located in the south of Minas Gerais state, got in the news [1] [pt] when lawyer Luiz Henrique Fernandes Santana petitioned for an immediate release of all prisoners in the city’s prison, arguing lack of space for all 248 inmates, since the prison could only effectively house 51. While the petition continues to be analyzed, general conditions in all Brazilian prisons [2] remain the focus of much debate.

According to a report [3] [pt] on human rights in Brazil, released in the beginning of this year by Human Rights Watch [4]:

Muitas prisões e cadeias brasileiras são violentas e superlotadas. Segundo o INFOPEN, Sistema de Informações Penitenciárias do Ministério da Justiça, a taxa de encarceramento no Brasil triplicou nos últimos 15 anos e a população carcerária atualmente é superior a meio milhão de pessoas. Atrasos no sistema judiciário contribuem para a superlotação carcerária: quase metade dos detentos está cumprindo prisão provisória.

[5]

[5]Porto Alegre Central Prison, considered the biggest prison in Latin America. Photo by Dr. Sidinei José Brzuska (used with permission).

With the intention of improving these conditions, Congress approved in mid-2011, Act 12.403/2011, which prohibits provisional arrests for sentences shorter than four years of imprisonment, and nearly 100,000 inmates were released shortly after its approval.

According to lawyer Doctor Joyce Royse, in an interview for the portal Meuadvogado [6] (Mylawyer) [pt]:

A Lei nº 12.403/11 tem por finalidade limitar o excesso de prisões processuais e criar medidas cautelares alternativas à prisão e que também sejam aptas a assegurar a aplicação da lei penal e a ordem processual. Nas entrelinhas, pode-se verificar que referida alteração legislativa também se deu por razões de política criminal, haja vista a caótica situação do sistema carcerário brasileiro.

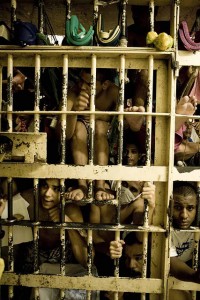

Vila Velha Prison Cell in the Vitoria City region, Espirito Santo State. Photo by Folha De S. Paulo (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The government has been investigating, however, how to improve this situation. In 1994, the National Penitentiary Fund [7] (Funpen) [pt] was created to finance and support the modernization and improvement initiatives of Brazil’s penitentiary system. A portion of its reserves comes from lottery profits, confiscated resources or resulting from the alienation of lost assets in favor of the country. A portion of such reserves, nearly R$ 350 million, is destined for the National Program for Support of the Prison System.

According to the site Portal Brasil [8] [pt]:

Por meio do Programa Nacional de Apoio ao Sistema Prisional, lançado em novembro de 2011, esses recursos vão financiar a criação de 42 mil novas vagas em penitenciárias e cadeias públicas, com intuito de zerar o déficit de vagas femininas e reduzir o número de presos provisórios em delegacias. O programa repassará para as unidades federativas, dentro de três anos, cerca de R$ 1,1 bilhão.

Despite the announced investments, the number of prisoners in Brazil almost tripled in the last 16 years, while the necessary infrastructure hasn’t grown accordingly. Accounts of deficiency and abuse in several prisons continue to be reported. In the beginning of 2011, all 97 inmates at Pinheiro’s jail, in the state of Maranhão, began a violent mutiny [9] [pt] demanding better conditions in all cells, constructed to accommodate only 30 prisoners. During the rebellion, six people were killed. A video [10] (containing graphic material) was recorded.

Similar reports also came from the state of Sergipe. According to newspaper Tribuna da Bahia [11] [pt]:

Uma inspeção realizada pelo CNJ (Conselho Nacional de Justiça) flagrou presos dormindo no chão ou sob toalhas pela falta de colchões e outras irregularidades em Sergipe. (…) No local, segundo o CNJ, existem presos que vivem há meses em uma situação insalubre. O interior das três celas é “acanhado e escuro a qualquer hora do dia”. (…) O banheiro fica no meio da cela, obrigando os presos a fazerem suas necessidades na frente de todos os colegas de cela.

The National Justice Council [12] has been conducting the Prison Initiative [13] [pt] in several states around Brazil, with the intention of,

fazer um relato do funcionamento do sistema de justiça criminal, revisar as prisões, implantar o Projeto Começar de Novo e, ao final, no relatório dos trabalhos, são feitas proposições destinadas aos órgãos que compõem o sistema de justiça criminal, visando ao seu aperfeiçoamento.

In a documentary [14] published on YouTube, (as reported [2] by Global Voices in February) the problems of the prison system are exposed through interviews with current and former prisoners, their families, guards, police officers, heads of prisons, human rights groups and others. Under the Brazilian Sun was directed and produced by Adele Reeves and Leandro Vilaca.

Since prisoners are stigmatized by part of Brazilian society, several of these problems remain unaddressed. Investments and improvements are certainly necessary, but while high amounts of money are invested, crime prevention policies take on a secondary role.

In a country where 1 in every 262 adults is in prison [15] [pt], solutions to assure a reduction of these rates are just as essential as the construction of new prisons.