This post is part of our special coverage on Refugees.

In recent weeks Global Voices has presented to its readers more examples of how citizen media is used to amplify the voices of refugees and displaced people. However, while blogs and social networking sites clearly have a role to play in empowering marginalized groups, so too do ICTs in general.

MobileActive, for example, is encouraged by the potential for mobile phones to allow refugees to not only remain in contact with loved ones, but to also more easily locate them. Attention is especially drawn to a special issue of Forced Migration Review which takes an in-depth look at the use of ICTs in this context.

Refugees in Uganda are using SMS and cellphones to reconnect with family members and close friends. Photo via MobileActive

Refugees often experience a compound trauma: The situation that caused them to flee in the first place, as well as the fact that many families become separated during migration. For refugee's health and well-being and ability to resettle, it is vital to know the whereabouts of relatives, their safety, and their ability to remain in contact. Today, mobile phones are the most important technology for refugees to find relatives and remain in contact.

The Forced Migration Review Issue 38, The Technology Issue covers technologies for refugees in particular. Two chapters shine a light on the use of mobile phones among refugees, as well as some of the problems with this tech to find and contact family member such as issues of security, and accessibility.

Deputy UN High Commissioner for Refugees T Alexander Aleinikoff provides an introduction to the special issue:

Superficially at least, today’s refugee camps do not appear significantly different from those that existed 30 or 40 years ago. Modernisation seems to have passed them by. But upon a closer look, it becomes apparent that things are changing.

Today, refugees and IDPs in the poorest of countries often have access to a mobile phone and are able to watch satellite TV. Internet cafés have sprung up in some settlements, the hardware purchased by refugee entrepreneurs or donated by humanitarian organisations such as UNHCR. And aid agencies themselves are increasingly making use of advanced technology: geographic information systems, Skype, biometric databases and Google Earth, to give just a few examples.

In one article, the example of a tracing project implemented by the Refugee Consortium of Kenya (RCK) in cooperation with Refugees United (RU) is highlighted:

In 1991 Ahmed Hassan Osman* fled the conflict in Somalia, leaving his family in Kismayu, and made his way to Kenya in search of asylum. Ahmed lived for a while in Ifo refugee camp before being resettled to Colorado in the US where he was granted full US citizenship.

In 1992, his cousin Abdulahi Sheikh arrived in Kenya in search of support. Granted refugee status, Abdulahi ended up in Dagahaley camp in Dadaab. He believed Ahmed was either in Dadaab or had been there but his efforts to find him were unsuccessful and he soon gave up hope of ever finding him. In fact, Abdulahi believed Ahmed had gone back to Somalia.

In early 2011 RCK employed Abdulahi to assist the RU project in Dagahaley refugee camp. Abdulahi registered with the tracing project and began a search for missing loved ones. Coming across a name that was familiar, he contacted the person through the RU message system. When he received a reply he realised that, after 20 years of separation and search, he had found his beloved cousin. They exchanged phone numbers and Ahmed called, breaking 20 years of silence. Today, the two keep in touch regularly and both Abdulahi and Ahmed continue to search for more friends and family members.

Of course, as MobileActive also stresses, some problems with local infrastructure remain an obstacle to the widespread adoption of such systems:

In some areas of Africa, there is no telecommunications coverage. Workshop participants commented that where it does exist, phone connections are regularly cut off, and some of them had also experienced intrusion in communication such as crossed lines. The strength of the network signal overseas is weak, and the lack of a reliable or steady source of electricity in a recipient’s country can be a major problem, although this varies by region. Growth of populations in some areas weakens network strength, due to the drain on power. Individuals may also have difficulty accessing electricity to charge their mobile phones.

[…]

Finding the best technology to use for different family members can be difficult, particularly if they themselves are displaced, because of factors such as the variety of available services, whether the family member could afford them and whether they have the skills to use them. One participant observed that the majority of their family members overseas needed to access communication technology through others. One participant described the difficulties she had in contacting her husband in a camp. She sent money to him to buy a phone but other people in the camp would also use it leaving her often waiting for hours to get in touch.

Cheap options such as email, voice-over-internet or instant messaging may not be accessible or affordable, and access to the internet in Africa is very expensive. Furthermore, displaced family members overseas may not know how to use these facilities.

From providing refugees with access to information on health and educational opportunities to using Facebook, Gmail Chat and Skype to maintain connections with family members and friends across geographical divides, the issue provides a comprehensive overview of how ICTs are being used.

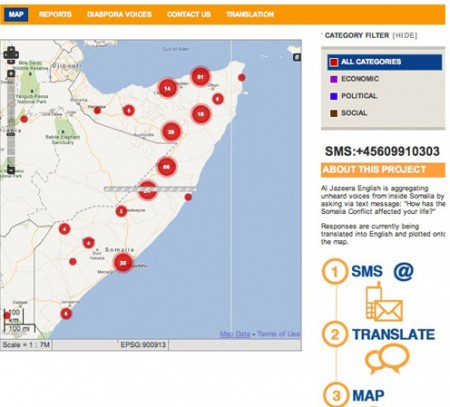

Ushahidi also gets a mention in relation to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti as well as in general as it pertains to conflict, disaster and refugees. Indeed, PBS’ Idea Lab takes a look at an Al Jazeera and Ushahidi collaboration to connect and empower Somalis separated by conflict and famine:

Somalia Speaks is a collaboration between Souktel, a Palestinian-based organization providing SMS messaging services, Ushahidi, Al Jazeera, Crowdflower, and the African Diaspora Institute. “We wanted to find out the perspective of normal Somali citizens to tell us how the crisis has affected them and the Somali diaspora,” Al Jazeera's Soud Hyder said in an interview.

[…]

The goal of Somalia Speaks is to aggregate unheard voices from inside the region as well as from the Somalia diaspora by asking via text message: How has the Somalia Conflict affected your life? Responses are translated into English and plotted on a map. Since the launch, approximately 3,000 SMS messages have been received.

[…]

For Al Jazeera, Somalia Speaks is also a chance to test innovative mobile approaches to citizen media and news gathering.

In October 2010, MobileActive also profiled a mobile-based project implemented by Refugees United in Uganda with the support of Ericsson, UNHCR and the Omidyar Network, noting that one blog called it “the social network that is more important than Facebook.”

The Technology Issue by Forced Migration Review can be read online here.

This post is part of our special coverage on Refugees.

6 comments

Why are Americans having to support the refugees?