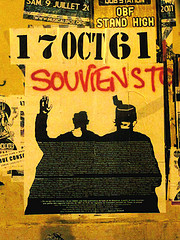

On October 17, 1961, in the midst of the Algerian war, the security forces from the Paris Prefecture of Police, under orders from Maurice Papon, cruelly suppressed a peaceful demonstration in the city by Algerians organized by the Fédération de France du FLN (National Liberation Front) [fr] to protest against the curfew specifically imposed upon them.

According to the historian Jean-Luc Einaudi [fr], at least 200 people of Algerian origin were killed – either thrown from bridges, shot, or bludgeoned to death. The press statement from the police chief reported the next day two demonstrators dead and several injured.

Fifty years later, these reported figures are the object of a controversial argument between the historians [fr] Einaudi and Brunet, and are still played down [fr] by right-wing politicians and historians, amid a deafening official silence.

The later police charge on the Charonne metro station on 8 February, 1962, which left eight dead, received much more attention. Now, people everywhere are speaking out and calling for the French government's admission of the 1961 tragedy.

Calls for government admission

On 12 October, 2011, the website Mediapart launched its online ‘Call for the official admission of the tragedy of 17 October 1961 in Paris‘ [fr], signed by a number of personalities as well as the full contingency of the French political left. The petition is still open:

The time has come for an official acknowledgement of this tragedy, the memory of which is as much French as Algerian. The forgotten victims of 17 October 1961 were working, residing, living their lives in France. We owe them this basic justice, that of remembering.

This 17 October (2011) some of the press were on the same wavelength. Le Monde.fr published online previously unseen photos [fr] from 1961, while OWNI published “accusing archives from the Prefecture of Police” [fr] under the heading “A French Shame 17 October 1961″, and on OWNI.eu, a graphic of the arrests made on that day.

Public radio service FranceInter devoted its broadcast “The March of History” to “The Police and North Africans in France, 1945-1961″, available on podcast here [fr], and France-Culture called its special report [fr] “The scar of the suppression of 17 October 1961″.

In an opinion piece published by Rue 89, the American historian Robert Zaretsky wrote [fr] as an introduction to his detailed account of the day of 17 October, 1961, and of its aftermath:

On 17th October, Nicolas Sarkozy's Gaullist government will not be aware of the fiftieth anniversary of a murderous event, shrouded in silence and confusion even today, that sheds crucial light on the complex relationship between the past and present, between the French and the Algerians in contemporary France.

In an interview with the historian of French colonialism, Gilles Manceron, the site bastamag.net tried to clarify the reasons [fr] for the French government's silence. According to Manceron, there had been a real desire to cover it up; he explains how the veil has gradually been lifted:

This was done on several occasions. In 1972, in his book La Torture dans la République (Torture in the Republic), Pierre Vidal-Naquet recalls the massacres of October 1961: “In 1961, Paris had been the scene of a real pogrom.” On 17 October 1980, Libération devoted a special report of several pages to it, entitled, “19 Years ago: a racist massacre in the centre of Paris”. In 1981, for the twentieth anniversary, Libération returned to the fray, followed by Le Monde. And for the first time, the events of 17 October 1961 have been discussed on television: Antenne 2 broadcast a report from Marcel Trillat and Georges Mattéi. In 1984, the novel by Didier Daeninckx, Meurtres pour mémoire (Murders for the record), also looked back on these events.

But it was so preposterous that these writings had no effect. It seemed implausible. Then came the 1990s, with the publication of the key work by Jean-Luc Einaudi, La Bataille de Paris – 17 octobre 1961 (The Battle of Paris – 17 October 1961), and the release of the film by Mehdi Lallaoui, Le Silence du fleuve (The Silence of the River). Young people who were children of immigrants picked up on this issue. All these factors and the different players led to the truth finally re-emerging.

Blogger BiBi was made aware of these events when reading Meutres pour mémoire, and commented [fr]:

Through those in power, France makes herself an arrogant sermoniser on history, the most recent lesson coming from Sarkozy. He rants and raves about the Turks and the Armenian genocide but there's no doubt at all that he has forgotten the murders perpetrated on 17 October 1961, the day when French Police, under orders from a certain Police Chief from the Seine by the name of Maurice Papon, threw Algerian opponents into the Seine when they came to protest against the unjust curfew which affected only them.

On the Bondy Blog, Chahira Bakhtaoui provides a commentary on a documentary [fr] by Yasmina Abdi, Ici on noie les Algériens (Here they drown Algerians), and Sarah Ichou interviewed [fr] her grandmother who was 27 years old at the time of the massacre, and her aunt who was eight:

When did you know what had happened? The next day and the following days, because there was no television. We knew then that there had been some deaths, that they had thrown Algerians into the Seine. I remember the sadness of the people surrounding me. Some men who went to demonstrate for their country, their independence and rights were killed and tossed into the water. So, it was dreadful, but we only learned of all this afterwards, that there had been dozens and dozens of deaths. It was the period of French Algeria. But everything I'm telling you is only the memories of a little girl 8 years old. I didn't know much about politics, but I did know that there was a war on, that we had to demonstrate for our country; I would hear it from the adults. I was living in this climate with my parents. I just have this memory of fear from this day, 17 October 1961. The proof that I remember it, is that it made a deep impression on me. In any case, in demonstrations there are always people who come to take revenge, to kill, to do whatever, because normally a demonstration is peaceful. People go to demonstrate for their rights and not to get themselves killed. On the other hand, those who came to kill didn't come to demonstrate. Those people are racists, they came because there was an Algerian demonstration, because there were Arabs, nobodies, so they needed to be dropped into the water, a page from history that's sad but unfortunately it's like that in all wars. That's the problem.

Médiapart has put online a map of the demonstrations [fr] that took place to mark the anniversary in France.

In Algeria, where a commemorative stamp has been issued, Akram Belkaïd on Slate Afrique recalls the Massacre d'État (State Massacre) [fr] and Afrik.com, the Nuit oubliée (Forgotten Night) [fr].

The editorial writer of El Watan meanwhile hopes [fr] to see “After denial, admission”, but it's October 1988 [date of democratic reform riots in Algeria] that another news writer remembers [fr], quoted by Courrier International.

@Celestissima was the source of several links in this post.

This text has been abridged and edited for English speaking audience.

2 comments

Always right-wing pigs downplaying mistreatment and injustice against minorities.

Then the selfish pigs save all their protests for immigrants and other minorities.

So, right-wing pigs downplay the murder of minorities, yet blow the hell out of proportion the presence of living minorities. It’s like 1+1=2. They are enemies of humanity, yet too stupid to realize they’re part of it, and eat, defecate etc, all the same. The main thing that sets those pigs apart from other humans is that they lack in empathy.