This post is part of our special coverage Mexico's Drug War [1].

In this third part of the summary for our Blog Carnival: Mexico – Citizenry, Violence and Blogs [2], we showcase posts that reflect on whether Mexican society is violent by nature.

Violence is a phenomenon with multiple manifestations –from armed clashes to verbal abuse– that are influenced by culture. But who establishes the variables that measure if violence has become a ‘natural’ part of society? Perhaps we should look at the fact that people seem to no longer be surprised or astonished with news about one murder, but they do react when they hear about the murder of hundreds. On the other hand, there seems to be a “fascination” with violent characters; a sort of game that legitimizes violence in a context in which people no longer trust the government.

In this summary we also include the posts investigating or showing the influence of violence on different expressions of popular Mexican contemporary art.

Is Mexican society violent by nature?

There is much talk about Mexico being a violent country [4]. Juan Ramon Anaya, from the blog deutschlango, seems to agree with this at some extent: he titled his post “Mexico, an armed movement every 100 years [5]” [es].

Cada vez que leo sobre los asesinatos resultado de la cruzada contra el narco emprendida por nuestro Felipe “corazón de” Calderón, no puedo quitarme de la cabeza la tesis de que todo fue un error y que simplemente se le salió de las manos, y que ahora estamos pagando todos los mexicanos, incluso sus allegados (recordemos el “accidente” de Muriño, secretario de Gobernación). Quizás sea el destino que llevamos en nuestra historia pues cada siglo se desata un movimiento armado : la independencia de 1810, la revolución de 1910 y ahora la lucha de Calderon de 2010.

Ariel Martinez Flores, from the blog Amblalluna, focues [6] [es] on another aspect of Mexican society that is causing violence: corruption.

Hubo un candidato a la presidencia de la República que acuñó la frase “La solución somos todos”, pero el mexicano común, el hombre de la calle decía jocoso e ingenioso: la corrupción somos todos” y esa generalización del fenómeno, fue el terreno fértil para el crecimiento de los grandes corporativos de la producción y distribución de drogas que a la sombra de la corrupción y la consecuente impunidad, crecieron y crecieron protegidos por funcionarios de todos los rangos y áreas del estado, hasta que llegó un momento en que ése estado se encontró en grave peligro de perder el control del país y no tuvo más alternativa que tratar de frenar a sus socios que amenazaban con quedarse con todo el negocio.

Rosalia Guerrero, from the blog Enluranada also refers [7] [es] to this issue, looking at day to day occurrences like piracy and crime:

Yo no sé ustedes, pero yo no quiero financiar a la delincuencia, por que la piratería hoy en día es una industria grande en la cual los que están detrás de no son los vendedores que nos reciben los 10 pesos por el disco sino la delincuencia organizada, que ocupara ese dinero no sólo para más discos sino para armas, balas y generación de narcóticos. Este es el punto de reflexión de esta columna, ¿Quieres financiar a los delincuentes? Por lo tanto ¿Hasta cuando seguiremos justificando nuestras acciones incorrectas?

Ian Keller, from the blog Tlacotzontli, does not agree with the idea that Mexico is inherently violent. He affirms [8] [es] that the past cannot be judged using the current standard, and that violence is not about nationalities.

este es un problema de la humanidad quitando diferencias de credo, de nacionalidad, de sexo o preferencias y para muestra vale solo un botón. ¿Recuerdan el ataque en Noruega, un país llamado del primer mundo, habitado por la gente más civilizada? Un fulano con problemas mentales severos se gestó en ese país a pesar de sus más altos valores sociales. Creo yo que la única forma de erradicar esta violencia es educar con valores a nuestros hijos, […] hablo de aquellos que nos hacen ser temerosos de Dios, de ese temor que inculca el respeto y obliga a hacer lo correcto por convicción propia; de hacer el bien y evitar el mal; de amar a los demás y tratarlos como nos gustarían que nos trataran. El mundo será diferente si en verdad trabajamos en depurar toda esa maldad que vemos en las noticias, en las películas, y en las novelas mexicanas.

Art, literature and music

Enrique Figueroa Anaya, from the blog Asfalto Tecnicolor, published a short story for the Carnival called “La Pasarela [10]“[es]. It is about women affected by violence, sometimes in an indirect way.

On the subject of creative writing, Ernesto Priego published a post [11] [es] in #SinLugar about poetry and violence, where he comments on the impact that violence has had in his writing process, and states:

México sufre diferentes tipos de violencia, que van de los más “sutiles” o transparentes y por lo tanto no siempre notados (por ideológicos, expresados en prácticas y actitudes culturales, usos de lenguaje, etc.) a lo más directos (feminicidio permanente, la guerra contra los drogas, crimen e inseguridad urbanas, etc.).

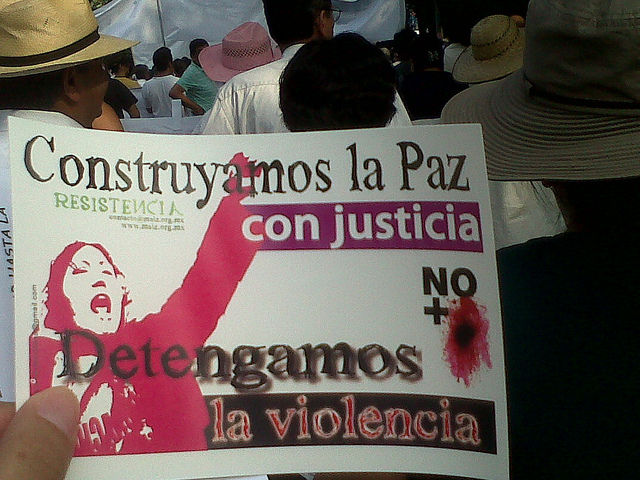

Art allow people to denounce or talk about violent events they have experienced. Art is also a form of resistance. Jorge Tellez talks about this in “Words of Violence” [12] [es] in #Sinlugar, where he mentions some initiatives that intend to portray reality through poetry and photography:

En México se dice que “ya estamos hasta la madre” de casi todo lo que importuna. Estamos hasta la madre de la contaminación, de los baches, del tráfico, de la selección, de la política, de la corrupción, […] Un claro ejemplo de esto es la campaña Alguien tenía que decirlo [13], cuyo propósito es el de documentar fotográficamente irregularidades que los habitantes de la ciudad de México viven diariamente, mediante la denominación de cada problema antecedido por la palabra “pinche”: Pinche bache, pinche tráfico, […] pinche violencia. […] Sí, de acuerdo: pinches drogas, pinche narcotráfico, […] pero ninguna de estas palabras supera el valor denotativo de nuestra indignación. Por eso iniciativas como la de 100 mil poetas por el cambio [14] aparecen este 2011 para darle un nuevo valor a la palabra y devolverle la connotación perdida.

Enrique Figueroa also shared images in two posts for the Carnival. The first one is called “Interferencia [15]” (Interference), with a picture by Alejandro Briseño [16] showing crosses in memory of murdered women contrasted with political propaganda. The second post, called “Silencio incómodo” [17] [es] (Uncomfortable silence) shows a picture by Jorge Alberto Mendoza [18], and Enrique explains why he chose this title:

(esta) imagen se me hizo representativa de lo que se vive en muchos sitios de México. La llamé ‘Silencio incómodo’ porque no se me ocurre otra forma para expresar lo que sentimos cuando vemos, escuchamos o leemos, sobre algún suceso violento que estremece a nuestro país.

Ernesto Priego also talks about the worldwide presence of the subject of Mexican violence in comics, and ironically about “The silence of the [Mexican] comic” [19] [es].

Como lector de cómics, defenderé siempre el potencial del medio para contar todo tipo de historias, pero como mexicano me preocupa que hasta ahora sea sólo la visión foránea y primermundista la que determine los discursos sobre la violencia mexicana. […] Los franceses obtienen becas para publicar un hermoso libro sobre Juárez, pero los mexicanos de Juárez quieren publicar en Estados Unidos y hacer películas y vender figuras de acción. […] La excepción que conozco al gran vacío narrativo en forma de cómic sobre la violencia en México es el trabajo de Édgar Clément [20].

On the subject of music, Enrique Figueroa chose [21] [es] several songs by Los Tigres del Norte [22], a Mexican band that tends to include a lot of social content in their lyrics. Enrique tells us that he chose this music because,

la música que acompaña a los mexicanos expulsados, aquellos que como bien dicen los Tigres del Norte [23], “mientras los ricos se van para el extranjero para esconder su dinero y por Europa pasear, los mexicanos que venimos de mojados casi todo se lo enviamos a los que quedan allá”.

Enrique also talks about cinema. In his post “Los Invisibles” [24] (The Invisible) [es] he links to a recently awarded documentary about Mexican migration with the same name.

This post is part of our special coverage Mexico's Drug War [1].