This post and Other Forest Stories are part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon and Global Development 2011.

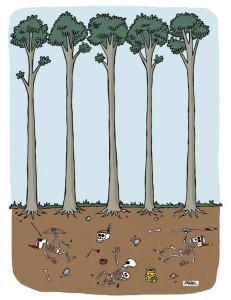

The term “green desert” was coined in Brazil at the end of the 60s, and refers to the vast monoculture tree plantations which were designed for producing cellulose. At this time, the term already alluded to the future consequences these plantations would have on the environment, including desertification, erosion, the elimination of biodiversity and human displacement.

The 60s saw the emergence of the first eucalyptus plantations in the north of the Minas Gerais state and in the south of the Bahia state. According to estimates from Brazil's forest farming association (Associação Brasileira de Produtores de Florestas Plantadas) in Brazil, 720 new hectares of eucalyptus monoculture plantations currently appear each day, which is equivalent to 960 football pitches. The most heavily planted areas are the Minas, São Paulo and Bahia regions, but the green desert is also spreading to other states in the north-east and the south of Brazil.

All the links in this post lead to Portuguese language pages, except when otherwise noted.

When travelling through the Minas Gerais state last April, the blogger known as the Viajante Sustentável (The Sustainable Traveller) spoke to inhabitants of the Jequitinhonha valley [en], and discovered how the region's visual and social landscape has changed over the last twenty years:

A catastrófica monocultura de eucalipto pelas empresas privadas nas cabeceiras dos rios e riachos, além de envenenar o solo, expulsou a fauna e flora do local, secou as nascentes e o lençol freático. O deserto verde do eucalipto tornou-se uma calamidade socioambiental. A região já foi auto-suficiente em alimentos essenciais, cultivados pela agricultura familiar, integrados com a natureza. A situação mudou radicalmente, exibindo riachos completamente secos, sem olhos d’água, rios cada vez mais baixos e assoreados, praticamente toda a alimentação proveniente de distribuidores em Belo Horizonte, pastos abandonados. Enquanto isso, as transnacionais de eucalipto e celulose engordavam os lucros.

In Montes Claros [en], the situation is no different:

Nada plantado, com a exceção lamentável de cerca de trinta quilômetros do triste deserto verde. As pragas do eucalipto e pinus se alternavam, envenenando, esgotando as nascentes e o lençol freático. Utilizando pouquíssima mão de obra, a monocultura de exportação em nada contribuía para a diminuição da miséria local, ao contrário, concentrava os lucros na mão de uma ou outra grande empresa transnacional.

Poet Anna Paim got a horrible shock when visiting her family home, the state of Espírito Santo, for the first time in 19 years:

Triste porque encontrei os mais belos locais de paisagem nativa totalmente destruidos e ocupados pelos eucaliptos. Deixo registrado aqui o meu protesto, a minha raiva, a minha pena, sei lá…

Beco da Velha (Old Woman's Alley) remembers natural eucalyptus as being very present in southern Brazil. He says, the damage began and worsened when GM plants were grown because they consume much more water, which causes them to grow at an accelerated rate:

O que há hoje de diferente no plantio do eucalipto, além de sua atual transgenia, é a intensidade com que isso se faz, a falta de qualquer critério ou bom senso na implantação das lavouras de eucalipto em qualquer lugar, em extensões assombrosas, e, principalmente, as intenções estratégicas que estão por trás dessa súbita paixão pelo “reflorestamento” – termo muito impróprio para o que hoje se faz, porque reflorestamento presume que se vai repor a floresta que existia no local, reconstituindo-se o ecossistema devastado. E é justamente o contrário que se passa.

Upwards and onwards

After spreading throughout the Atlantic jungle in the southeast, the green desert arrived in the arid zones in the north and northeastern areas of the country. In Piauí, the construction of a paper and cellulose factory comes with a promise of development for the state. This is contested by blogger Leo Maia, who argues that according to facts from IBGE (The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), 41% of the state's population is malnourished, while local farmers do not have the incentive to grow food.

Despite this, 160 thousand hectares of Piauí land (equivalent to 1 600 km² or 1.57% of Piauí land) was transformed into eucalyptus “forests” in order to produce paper and cellulose for export. In his blog, Leo republishes an article which appeared in a local newspaper and denounces the contrast between commercial interest and the needs of the population:

(…) árvores de crescimento acelerado, como o eucalipto, dependem de grande quantidade de água para se desenvolver e por isso provocam o secamento do solo, diminuem os mananciais e aumentam a possibilidade de desertificação dessas regiões. Sendo assim, a instalação da Suzano mais uma vez contradiz as reais necessidades da população do Piauí, já que o estado sofre, praticamente todos os anos, com os efeitos da estiagem. Só no início deste ano, mais de 155 municípios declararam estado de emergência por causa da seca, alguns deles tiveram a safra comprometida em 90% por falta de água.

Environmentalists and social campaigners still denounce the risk that the dangerous combination of eucalyptus, monoculture and pesticides has on people's health. Besides occupying land which could be used for agricultural purposes, growing eucalyptus even hinders those who farm food in nearby regions, because their land ends up being invaded by wild animals in search of food. Mariana Brizotto highlights the fact that plantations are not forests and asks:

O que faremos quando não houver mais água? Vamos comer papel?

Despite farmers losing land to the eucalyptus monoculture, Bahian Sumário Santana‘s poetry draws inspiration from the sadness and beauty of the green desert:

Onde existia uma comunidade tradicional, de nome Marília, hoje é a fábrica de Celulose. Ali em Mundo Novo, onde trabalhavam contentes as famílias com as suas pequenas olarias, hoje existe apenas uma grande olaria. Foram embora as famílias, secou o rio, sumiu a argila e agora, a fábrica ameaça fechar. Ali onde antes era uma colônia agrícola, com centenas de pequenos proprietários, hoje são latifúndios cercados, guardados por seguranças de motos.

Ali onde era imensa, diversificada e úmida a floresta, hoje é um deserto verde.

O supostamente feio, caótico e emaranhando de plantas, cipós, nascentes, bichos, ninchos, centopéias, gosmas, barro, limos e fotossíntese, deu lugar

Ao supostamente belo, um único mosaico, bem desenhado, mapeado, registrado, uma única espécie, repetida em série, na solidão do deserto.

There is now a Cellulose factory where the traditional community of Marília once existed. There, in the New World, families happily worked in their small brickyards. Now, there barely one large brickyard left. The families left, the river dried up, the silver disappeared and now the factory is threatened with closure. Instead of the farming colony with hundreds of small-scale owners which was there before, there are now large estates nearby which are guarded by motorbikes.

Instead of an awesome, diverse and humid forest, there is now a green desert.

The supposed ugliness of chaotic, tangled plants, lianas, springs, insects, bugs, centipedes, slime, mud, silt and photosynthesis gave way

To the supposed beauty, of singular, well-designed, mapped out, patented mosaics: One single species, repeated in sequence, in the desert's loneliness.

This post and Other Forest Stories are part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon and Global Development 2011.

![deserto verde Good bye, my pampa [bioma]. In the background, an eucalipto plantation.](https://pt.globalvoicesonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/santiago_pampa3.jpg)

3 comments