This post is part of our special coverage Indigenous Rights [1].

Taiwan's indigenous population are often flattered by politicians as being the country's “real masters” or “original inhabitants”; they have been used to promote Taiwan tourism in television commercials around the world.

But stories about their struggle for identity, sustainability and dignity are missing from the Taiwanese public sphere, as a result of relative social and political domination by the country's Han Chinese population. Now, thanks to social media, indigenous youth are making their voices heard and reconnecting with their traditions.

Indigenous Taiwanese. Photo by Senayan, used with permission.

“Tribal Grid”

A group of ambitious indigenous Taiwanese writers and bloggers first started a group online blog called Blogger Check-in [2] (部落客報到) [zh] in October, 2010. In Taiwanese the word “blog” in fact translates literally to mean “tribal grid” (部落格) and the word “blogger” into “tribal people” (部落客).

Besides the blog, the group have multiple outlets to effectively spread their news, including social media such as networking site Facebook and micro-blogging site Twitter, as well as independent online media sites such as Lihpao [3] [zh] and PNN [4] [zh].

In the past, in order to enter mainstream society, many indigenous people preferred to register their name in Han Chinese when processing official documents, such as identity cards. However, practices such as this have only served to further marginaliz ethnic minorities in Taiwan.

Snaiyan (思乃泱) talks on Blogger Check-in about the benefits of using ethnic names on Facebook [5] [zh]:

原住民人口比例佔臺灣總人口比例極少,常使得原住民在做的事情、所關心的事情經常被忽略。使用原住民姓名的人數若更少,就更會讓人忽視原住民參與在大社會與各式社群的存在,成為隱姓埋名的一群人。我可以理解,現實生活中要改名的困難,尤其是對於年紀越大的人來說,不只身分證、駕照、帳戶、護照、戶籍等等,還包括已建立的知名度等等,要重新開始一個早該經營的開始,實在有困難。那麼若從網站社群的世界開始使用原住民名字,應該也可以當作是另一個開始。

使用FB以來,我發現一個很有意思的改名現象。例如某位原住民年輕人向來使用漢名,可能之後他會在漢名後面括弧註明自己的原住民羅馬拼音名,讓人認識他的族群背景;或者一夕之間就把羅馬拼音名直接取代成正式的註冊姓名,後面才括弧漢名。改名後,他的原住民朋友因此感到好奇,詢問要怎麼改名呢,於是也跟著把自己的名字改為與家族有連結的姓氏。很可能現實生活中,他們身分證上的名字仍舊是漢名,但是透過FB開始改名,讓周邊以及往來聯絡的朋友先習慣這個名字的存在,也習慣連結他們及其背後部落族群的存在,也是一種在社群當中公開表明自己身份的方式。

更有意思的是,我有好幾位很愛跟部落在一起的白浪朋友,在FB註冊時根本就是直接註冊自己被部落族人給予的原住民名字;或是在漢名之後括弧註明自己的原住民名,標明了他們與部落之間的緣分與關係,這些都有助於連結原住民群體標示的存在。

Protecting Indigenous Rights

Snaiyan also reflects [6] upon the condition of Taiwan's indigenous people after watching “Ryomaden [7]“, a Japanese television drama about Sakamoto Ryoma [8] (坂本龍馬), a visionary hero:

不講整個臺灣政治,就單一部落來講,我們更是欠缺像龍馬這樣不為自己只為部落的人才,願意致力以部落未來為前提去與大家溝通,在部落四分五裂的矛盾意見中統合出一個可以前進的作法。常常看到的是,部落有各種協會、組織等山頭,或是以各家族勢力與利益為處事前提,或是以教會派別區隔傳統行事參與,中青輩可能不信任長老輩做的決定,長輩認為年輕人努力得不夠,於是不願意朝彼此接近、只是用自己的想像持續去猜測對方……明明外面的人看到的是一個部落,然而內部卻是暗潮洶湧、驚濤駭浪。在缺乏共識的結果下,當部落需要達成一個可以對內對外表達集體決定的時候,因此延宕,造成被局勢決定的命運。

Senayan (斯乃泱) from the Likavung Tribe is more optimistic about her own group because of the active participation [9] [zh] of enthusiastic community members in the public affairs of the tribe:

在部落從事公共事務,來參與清掃的這群人幾乎是基本咖,活動中幾乎都會看見他們熟悉的身影,「部落」就是要有這樣的一群傻子才可以成事。部落組織運作目前雖不完善,但有這樣一群願意為部落付出的人,大家應該感到欣慰與給他們多多鼓勵或回以美麗的笑容或問候或一起參與。

It is very important for indigenous groups in Taiwan to reach build solidarity among themselves as many of the policies, manipulated by legislators and politicians in central government, are threatening their joint future survival, such as the new Eastern Taiwan Development Act, which justifies the de facto seizure of indigenous people's land under the pretext of “development”.

Shih Shen-wen (施聖文) criticizes the new Act [10] [zh]:

在《東發條例》中,簡化土地處理的程序,並不是拉近人與土地之間相互依存的親近性,反而是將這套商品生產剝除了神祕面紗,轉變成為權力、資訊與資源的爭奪場域。可以想見,未來在所謂「東永小組」還是其他的上位組織,來決定未來花東地區的「重大建設」時,決定的是各種開發提案的文件工具的齊備,以及如何完備、符合條例用畫大餅的政治語言勾勒出來的目的。

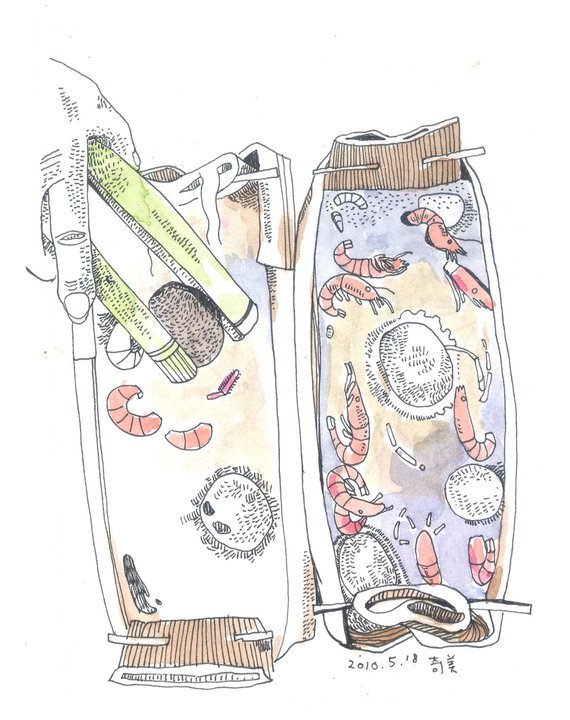

Stone hotpot of Chih Mei Tribe. Painting by Shauwen Tsai, used under permission

Many Taiwan Han Chinese enjoy “helping” the indigenous people by introducing modern development plans or teaching the children modern culture. Ligelale Awu (利格拉樂.阿烏), who was a college professor, criticizes the College Students’ Mountain Services [11], a student society which mobilizes students to do voluntary work in indigenous areas.

Awu points out that, instead of appreciating the indigenous culture, the Han college students keep teaching the kids “how to play” with city toys and how to speak Taiwanese.

Falahan (法拉汗) from the Chih-Mei Tribe invites his readers to visit his tribe and explore the origin of Amis people through their natural cuisine [12], as a way to develop the understanding of indigenous cultures.

As the indigenous blogoshere in Taiwan grows, the communication barricade between Han people and indigenous peoples is gradually being lifted. Yet more mutual understanding is absolutely necessary.

With the help of bloggers from Blogger Check-in and other indigenous friends on social networking sites, I will help by bringing Taiwanese indigenous voices to the readers of Global Voices [13] from time to time.

This post is part of our special coverage Indigenous Rights [1].