This post is part of our special coverage Languages and the Internet.

The Portuguese language, spoken by more than 200 million people around the world, has often been described as the “fatherland” or “motherland” of the Portuguese-speaking world. On February 21 we commemorated International Mother Language Day, established by UNESCO in 1999. In a tribute to the Portuguese language in all its linguistic and cultural diversity, we invite you in this article to navigate through reflections from Portuguese-speaking bloggers, prompted by their reading of the first novel dedicated to the Portuguese language [pt], Milagrário Pessoal – the most recent work by the Angolan author José Eduardo Agualusa.

The title of this article was taken [pt] from the blog Mértola, in which Carlos Viegas writes that Milagrário Pessoal is:

uma declaração de amor à língua portuguesa, na sua multiplicidade de falares (…) uma viagem pela história da nossa língua, pelos locais e culturas que alimentaram a sua enorme riqueza.

Portuguese is the official language of eight countries – Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe and East Timor – in four continents – Africa, America, Asia and Europe. Thus, the language covers a vast area of the Earth's surface (7.2% of the planet [pt]), encompassing an extraordinary diversity of lives which is reflected in the variety of dialects. It is also the fifth most spoken language on the Internet, according to Internet World Stats, with around 82.5 million internet users. Deceased in June 2010, José Saramago – the only Portuguese-speaking winner of the Nobel prize for Literature – said that “there is no Portuguese language, but rather languages in Portuguese ” [pt]. The writer Agualusa, in an interview [pt] with the blog Porta-Livros, states that:

O português é uma construção conjunta de toda a gente que fala português e isso é que faz dele uma língua tão interessante, com tanta elegância, elasticidade e plasticidade.

The novel – or the “essay on the Portuguese language disguised as a novel”, as the journalist Pedro Mexia describes it in a critique entitled Politics of Language [pt] – simultaneously tells a love story and explores the processes of construction of the Portuguese language. Agualusa, again in the afore-mentioned interview, confesses to “greatly regretting the disappearance of certain beautiful words which fall out of usage” and shares the necessity and “obligation to prevent the death of these words”.

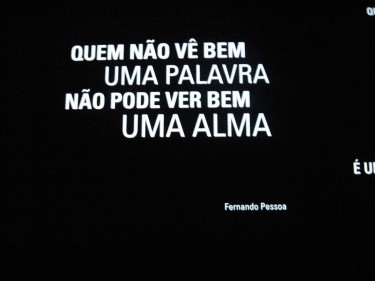

Poem by Fernando Pessoa: He who cannot fully perceive a word, can never fully perceive a soul. Photo: Lu Freitas on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rui Azeredo, from the blog Porta-Livros, explains [pt] that the “[love] story serves solely as a pretext for the author to pay homage to the Portuguese language” :

através de uma busca, por parte das suas principais personagens, dos neologismos do português. E bem encaixados no meio da história (…) surgem os neologismos, como uma aula na qual nem se repara, mas onde tudo se aprende. De Portugal a Angola, passando pelo Brasil e outros, corremos os olhos por jogos de palavras (novas e velhas, dependendo por vezes da geografia) bem lançados por Agualusa.

In a summary [pt] of Milagrário Pessoal, Bruno Vieira Amaral, from the blog Circo da Lama, considers that “words have power, words are power”. Amaral comments on excerpts from Milagrário Pessoal - in quotes as fanciful as they are representative of the countries to which they refer – in which the Portuguese language serves as a vehicule for refractory, subversive and nationalist political practices:

Palavras também são poder, política no sentido mais lato. Podem significar insubmissão, como no caso do timorense que declamava sonetos de Camões. Podem significar afirmação nacionalista, como no caso das elites brasileiras que passaram a utilizar apelidos de origem tupi. Podem significar subversão, como o colonizado que pretende colonizar a língua do colonizador para assim o dominar.

José Leitão, in the blog Inclusão e Cidadania, supports this view [pt]:

O romance contém pistas preciosas para uma política da língua, que merecem a atenção dos cientistas sociais, dos linguistas e dos responsáveis pela política da língua portuguesa.

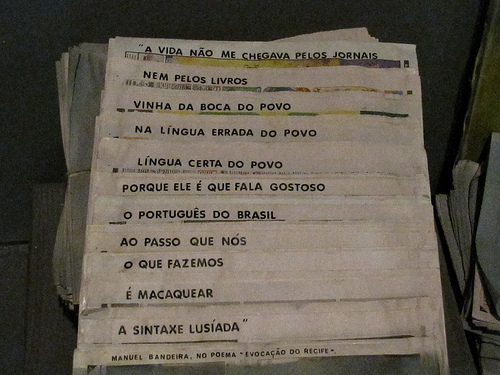

Poem by Manuel Bandeira: Life did not come to me through newspapers nor through books/It came from the mouth of the people in the incorrect language of the people/Correct language of the people/Because it is the people who delight in speaking the Portuguese of Brazil/While in the meantime/What we are doing/Is mimic/The Portuguese syntax. Photo by Capitu on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The reflections of Milagrário Pessoal‘s readers in the blogosphere at times broach the subject of the controversial Spelling Reform of the Portuguese language, which aims to unify and converge the different spellings used in each Portuguese-speaking country. In his interview with the blog Porta-Livros, Agualusa states:

Nunca como agora houve tanto movimento de pessoas e ideias entre todos os países de língua portuguesa. (…) E isso faz com que a língua se aproxime.

Pedro Teixeira Neves, of PNETLiteratura, quotes [pt] a passage from the book and asks:

«Escreve Moisés da Conceição que a língua portuguesa, sendo já africana na sua matriz, pelo demorado convívio pelo árabe, que muito a contaminou, necessita de enegrecer ainda mais, afeiçoando-se à geografia dos lugares onde estão os seus abundosos falantes. O nosso destino é o de nos engolirmos uns aos outros…» Resumindo, é pois, de algum modo, esta a temática-tese de fundo onde se inscreve a tinta ficcional deste romance. Crítica velada ao acordo ortográfico? Porque não entreler desse modo?…

Offering no response to his question, Teixeira Neves states that “language is a treasure” [pt] and concludes:

Um tesouro guardado não numa arca estanque dos povos que dele fazem uso (portanto, que falam essa Língua, o português), antes um tesouro que na sua diversidade geográfica e crescimento contínuo mais se enriquece e inflaciona. Em suma: a identidade da língua é múltipla, e tal facto não representa senão um acrescento, jamais uma subtracção. A língua é elástica, corpo vivo que se alimenta do tempo e dos tempos. A língua é uma contínua viagem de navegação por mares a cada dia nunca antes vistos ou adentrados.

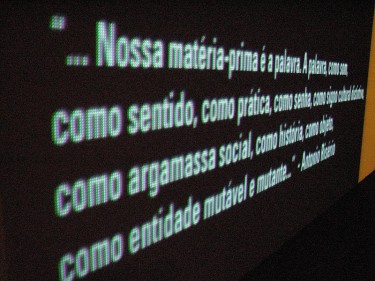

Poem by Antonio Risério: “our raw material is the word. The word as a sound, as a sense, as a practice, as a password, as a cultural indicator, as cultural cement, as history, as an object, as a changing and changeable entity

This post is part of our special coverage Languages and the Internet.

4 comments

Thank you Eleanor for taking the challenge of translating this post!