This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].

On August 26 the President of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva [3], signed a decree that transfers the concession to harness the hydroelectric potential of the Belo Monte Dam [4] on the Xingu River [5], in the State of Pará [6], to the Norte Energia consortium [7][pt], over approximately 35 years, while also authorizing the commencement of construction work. This is a controversial move [8][pt], involving an investment of 19.6 billion reais and the potential for supplying 26 million people with energy, at the cost of deforestation, flooding towns and displacing thousands of people. The government’s action is calculated to give the impression that the Belo Monte project is being conducted under completely normal conditions and that the construction of the dam is inevitable. Behind the scenes, however, the events suggest something rather different.

Behind the government’s official talk of “normality”, people have been organizing themselves into social and environmental resistance movements [9][pt] against the construction of the dam since the 1970s. They are made up of Indians and river dwellers whose present way of life and means of survival will suffer a disastrous impact if the dam is built.

Indigenous people and river dwellers from all over the area of the Amazon where the hydroelectric plant is being planned have joined together to try to establish common strategies to halt the damming of rivers in the Amazon region. These groups are fighting to be heard in order to raise public awareness and encourage people to join forces with them in demanding the interruption of the project before the construction phase of the dam. This is aimed at promoting dialogue, hitherto virtually inexistent, between stakeholders and those affected by the construction of the dam.

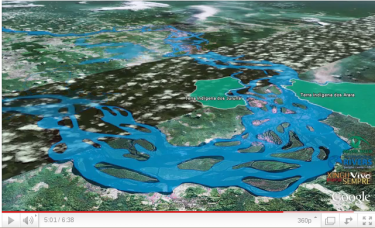

[10]

[10]UHE Belo Monte, by Flickr user J.Gil shared under a CC license: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

They are counting on the support of people committed to indigenous and environmental causes. One such individual is Right Livelihood Prize [11]for his decades-long work as an activist for indigenous rights. Kräutler, Bishop of Xingu, Pará, and President of the Indigenous Missionary Council, says [12] [pt]:

Sou contra o projeto do jeito que foi feito, com autoritarismo e preconizando o discurso desenvolvimentista do governo que só fala das vantagens e nunca das desvantagens que Belo Monte trará. Cerca de 30 mil pessoas serão chutadas de lá [da Volta Grande do rio Xingu] e levadas sei lá pra onde. Essa obra vai ser a maior agressão já vista na Amazônia.

Also committed to the cause, and one of the leaders of the case brought to the Federal Ministry of Pará, is the attorney Felício Pontes Júnior, who filed his first lawsuit against Belo Monte in 2001, ensuring that the project has not seen any action since then. Had he not done so, the plant would have been built by now. In total, the Federal Ministry of Pará has seen eight cases which deal with the trampling of legal procedures and point out irregularities in the dam’s environmental licensing. None of these claims had come before the court by September 2 this year, which shows that only a court order can change the game.

According to Pontes Júnior, the government is trying to the “fait accompli tactic”, which in law refers to the attempt to circumvent lawsuits by the idea that once work has been completed, it cannot be reversed. However, the ongoing cases may still be able to prevent the construction of the plant:

O governo federal tem soltado release sobre Belo Monte como se o fato já estivesse consumado. Temos processos em andamento que, se tiverem decisões favoráveis, nós paramos Belo Monte. (…) Nós não desistimos de barrar Belo Monte. Queremos barrar a construção da hidrelétrica sim porque todos os estudos, da Unicamp, da USP, da UnB, mostram que é uma obra inviável. (…) Nós não estamos jogando a toalha.

The news about Belo Monte reported on EcoAgência [13] on September 27 shows that Pontes Júnior has not given up the fight. He and his colleague Cláudio Terre do Amaral attended a meeting on September 24 with the representatives of the approximately 12 thousand families living in the Volta Grande area, which covers 100km of the Xingu River in the Vitória do Xingu municipality. Two opposing processes have been precipitated in this region by the construction of the plant: the disappearance of water and the formation of a lake along one stretch of the river, and the resultant flooding along another. Both phenomena are devastating for families who survive from fishing and small-scale farming, and who still do not know what will happen to their land and property if the plant is built. Pontes Júnior explains:

Ainda falta muito para que a usina se torne uma realidade, mas estamos preocupados com o fato dessas famílias não terem recebido informações concretas sobre o empreendimento.

These families cannot even count on actually benefiting from electricity. One of their complaints is, quite justifiably, the lack of electricity, despite the Volta Grande region being only 300km from the Tucuruí dam. The electricity distribution company has already informed the farmers and river dwellers that the Light for Everyone programme will not reach the residents of the inlets that will be flooded if the dam is built.

Under the heading “Attorney fears confrontation at Belo Monte dam site”, the Indymedia [14] [pt] blog reports Pontes Júnior’s concern that there may be a confrontation between the indigenous people and construction site employees once work is underway:

Eu estou extremamente preocupado. Porque o discurso dos indígenas está sendo no seguinte sentido: “Nós vamos morrer de qualquer jeito se esse rio [Xingu] for barrado, então nós vamos morrer lutando”. Temo por um conflito no canteiro de obras dessa hidrelétrica, entre os índios e os trabalhadores da construção civil. Isso pode acontecer e, pessoalmente, é o que mais angustia.

Despite all these impacts and problems, the indigenous people reaffirmed their stance on the construction of the dam in December 2009, as reported in the Brasil Autogestionário [15] [pt] blog:

Nós, povos Indígenas, não vamos sentar mais com nenhum representante do governo para falar sobre UHE Belo Monte; pois já falamos tempo demais e isso custou 20 anos de nossa história. Se o governo brasileiro quiser construir Belo Monte da forma arbitrária de como está sendo proposto, que seja de total responsabilidade deste governo e de seus representantes como também da justiça o que virá a acontecer com os executores dessa obra; com os trabalhadores; com os povos indígenas. O rio Xingu pode virar um rio de sangue. É esta a nossa mensagem. Que o Brasil e o mundo tenham conhecimento do que pode acontecer no futuro se os governantes brasileiros não respeitarem os nossos direitos como povos indígenas do Brasil.

In the same interview, Pontes Júnior revealed that at the meeting of indigenous people on August 26 they decided to approach the international courts and ask them to denounce the violation of their rights:

Eu espero que, com essa decisão, nós consigamos o apoio internacional, principalmente das entidades ligadas aos direitos humanos, e também das entidades técnicas, a Comissão Mundial de Barragens, por exemplo. Estudos técnicos, por exemplo, podem comprovar a inviabilidade econômica dessa hidrelétrica.

This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].