This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].

[2]

[2]Photo by flickr user Lorena Medeiros, published under anAttribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Creative Commons License

The idea commonly supported in the collective Brazilian imagination, that the indigenous Brazilian is no longer considered indigenous as soon as he or she adopts the customs and technologies inherited from the West, is countered by a reality in which indigenous villages are using information tools and technology with ever more frequency precisely for more efficiently defending their indigenous lifestyle and culture.

In Taqui Pra Ti [3] [pt] blog, an article by Professor José Bessa Freire, coordinator of the Indigenous Studies Program (University of Rio de Janeiro) [4] [pt] and research with the Graduate Program in Social Memoy (UNIRIO) [5] [pt] discusses the indigenous appropriation of citizen media available online and the use of multimedia content to promote socialization, claim rights and affirm indigenous identity in cyberspace:

No Brasil, índios de diferentes línguas e etnias foram estimulados a usar a Internet por organizações governamentais e não governamentais. Embora a situação ainda seja bastante precária, inúmeras das 2.698 escolas indígenas existentes nas aldeias, frequentadas por mais de duzentos mil alunos, foram dotadas de computadores. Ali onde isso não foi possível, os computadores dos postos de saúde da Funasa foram disponibilizados dentro dos Pontos de Cultura no Programa Governo Eletrônico [6] – Serviço de Atendimento ao Cidadão.

With increased computer access, the first indigenous internet sites began to appear in 2001. According to Eliete Pereira, from the Atopos Research Center at the Arts and Communications Faculty of the University of São Paulo [7] [pt], indigenous presence on the internet is still rather erratic [8] [pt]. In a map she prepared of indigenous internet participation [8] [pt], Eliete found three types of sites: personal sites, sites corresponding to particular ethnicities and sites corresponding to indigenous organizations.

Holders of personal sites innovatively used the internet to show individual indigenous production. In this category, for example, we find the sites of writers Daniel Munduruku [9] [pt] and Eliane Potiguara [10] [pt], in which the authors present their books and interact with their readers. We also find the blogs of notable indigenous leaders like Ailton Krenak [11] [pt].

The sites pertaining to specific ethnic groups have been designed to bring greater domestic and international visibility to particular indigenous ethnicity through the dissemination of arts, indigenous craft art, design patters, narratives and languages of different ethnic groups. This is the case of the Baniwa [11] [pt], the Ashaninka [12] [pt] and so many others who, after participating in the discussion on indigenous access to information technology and the internet in 2005 in Rio de Janeiro, and following the inauguration of the People of the Forest Internet Portal [13] [pt], began to use these digital tools as part of interculturally-based educational projects supported by the Ministry of Education (MEC) [14] [pt] and NGOs like The Socio-Environmental Institute [15] [pt].

Finally, the sites created by different indigenous organizations are presented online by institutions that represent different ethnic groups, that cover local, regional or national collectives, and that are associated with the fight for land rights, bilingual education and the health of the indigenous population. These sites are tools for claiming rights and pursuing political action. Examples include The Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB) [16] [pt], the Online Indigenous Brazilians [17] [pt] and the Federation of Indigenous Organizaiton of the Back River Region (Rio Negro) (FOIRN) [18] [pt].

The Suruí, information technology and the Amazon Rainforest

A very successful case of political action focussing on the use of digital technologies is the initiative pursued by Almir Narayamoga Suruí [19] [en], chief of the Gamebey tribe of Suruí Indigenous Brazilians [20] who live in the indigenous village of Sete de Setembro in the state of Rondônia, Brazil. The forest has always played an important role in the lives of the Suruí, both from a cultural point of view and from an economic one, which is why Almir's tribe is engaged in reforesting and in combating deforestation of the ancestral lands through the use of tools like Google Earth and GPS.

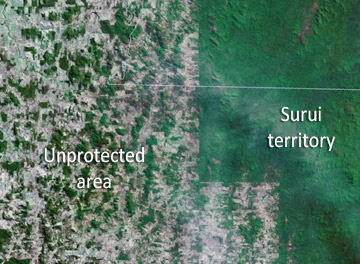

In his first consultation in 2007, Almir endeavored to find his village in Google Earth's satellite image. That was when he immediately noted how much of his people's territory was being threatened by the rampant deforestation of the outlying forest. Yet, at the same time as he grew worried about what he had found, he also noticed that the solution was just before his eyes; the internet could give the Suruí the visibility and cultural strength needed to protect the forest.

Images of Surui land as seen from Google Earth [23]

A partnership with Google Outreach [24] – Google's social arm, and the Metareil'a indigenous association [25] was signed soon thereafter in 2008. The first tangible result of this partnership [23], the so-called cultural map, was made available to internet surfers (using Google Earth), including to Suruí internet surfers. With the technical assistance of ACT-Brasil [26] [pt], the map was prepared based on information collected in conjunction with the Suruí elders and wise men who were familiar with the history and characteristics of the tribal territory.

For Almir, the relationship between Suruí and the internet, this “tool of the white man,” is an innovative attempt to ensure that “contact” reinforces, not corrupts, indigenous lifestyle. In the case of the Suruí, their first contact [27] [pt] with the European-influenced culture and society of Brazil occurred in September 1969:

[Há] apenas 40 anos os primeiros homens brancos penetraram em nossa floresta. Cheios de esperança, recebemos estes visitantes com a intenção de estabelecer relações de paz com o mundo externo. Contudo, nossa esperança para o futuro se deparou com imensa tragédia. Apenas dois anos depois do primeiro contato, a população Suruí diminuiu de 5.000 pessoas para 290. Além de muita gente nossa morrer devido a doenças novas para nós, nossa cultura foi ameaçada de extinção por causa da morte de nossos anciãos. Aos 17 anos, assumi o papel de chefe. Hoje, busco apoio do mundo externo, com esperança renovada.

According to the NGO Aquaverde [28] [pt] the Suruí have been “precursors” and “an example” for other indigenous groups in the efficient fight against invaders and destroyers of their lands, but

[e]ste sucesso ainda é frágil e ameaçado, precisa se consolidar, mas o desmatamento não progride mais nas terras Suruí. Infelizmente, várias áreas foram profundamente afetadas pela falta da floresta. No entanto, os Suruí conseguiram se libertar da dependência dos madeireiros, voltar às suas atividades tradicionais e desenvolver novas, tais como: piscicultura, cafeicultura e artesanato.

Surui Cultural Map

A second initiative has been technology training for approximately 20 indigenous Brazilians in the association`s headquarters in Cacoal. A third step will pursue the more ambitious stage of the “partnership” to use internet resources: combatting the deforestation of the Sete de Setembro Reserve in real time. In order to achieve this, the Suruí will be given smartphones that are equipped with Google's Android system, which will enable them to capture occurrences of deforestation in real time, post images on the internet and send them to the world and to the proper authorities.

The argument that indigenous identity is lost on account of the adoption of digital technologies thus becomes baseless. In fact, the Suruí intend to strengthen their right to preserve, to the greatest extent possible, their relationship with the earth and the culture inherited from their ancestors.

See a video: Trading Bows and Arrows for Laptops [30]

This post is part of our special coverage Forest Focus: Amazon [1].