If “hanging chads” and faulty computer chips are causes for concern in today's elections, just imagine the likely fraud that took place in Classical Athens when residents often used small pebbles to cast (literally) their votes. The study of those pebbles, or the votes they represent, developed into an entire academic discipline, Psephology. (Psephos, or ψῆφος, is literally “pebble” in Greek).

But then, Classical Athens in the 5th Century BC was made up of only around 30,000 eligible voters. (The vast majority of Athenian society was comprised of slaves without civil rights; women also could not vote or own property.) With just 30,000 participants, Athens could be governed by direct democracy. Adult Athenian men did not elect representatives to vote on their behalf, but voted on legislation and executive bills in their own right. Today's average national democracy, in comparison, attempts to govern over 30 million individuals. The federal government of India, the world's most populous democracy, governs over one billion citizens. It is simply neither practical nor possible for each of those billion voters to take part in every legislative decision.

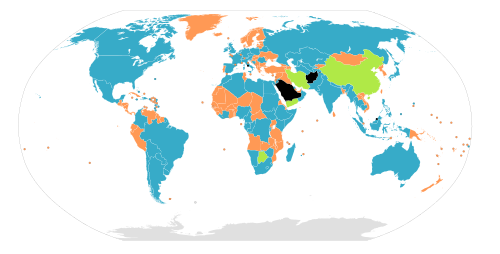

Blue – Nations with bicameral legislatures.

Orange – Nations with unicameral legislatures.

Gray – No legislature.

As a result, we almost all live in representative democracies where we elect public officials to create and vote on legislation on our behalf. This layer of representation, while necessary, takes citizens away from the decision making process. For decades broadcast media provided just about the only link between citizens and their elected representatives, but coverage tended to focus more on the lives of the politicians and less on the issues they vote on. Over the past five years a new generation of websites have sprouted up which combine information from parliamentary websites with social media tools in order to give citizens more information and clarity about the profile and activities of their representatives, and to become more active in the legislative process.

You can see all of the parliamentary informatics projects we reviewed at the Technology for Transparency Network by clicking on the “parliament” filter underneath the map interface.

Parliamentary Informatics

The first such website we reviewed is Vota Inteligente, a project of the Smart Citizen Foundation in Santiago, Chile. Like most of the parliamentary informatics websites we documented, Vota Inteligente “scrapes data” from the websites of Chile's Senate and House of Deputies in order to more effectively gather and present information about representatives, political parties, and legislative bills. Using the information gathered by the Vota Inteligente team, you are able to compare congressional terms by party, gender, age, and incumbency. There is also a section called “Informed Citizen” which provides contextualization and analysis of the large flow of information that is added to the website every week. The website's archive presents access to all collected data and documents. It includes a glossary, source list, document library, multimedia library, and collection of legal and legislative documents.

Vota Inteligente depends on Facebook and Twitter to sustain interaction with its users. The team has also started a “webinar” series where invited guests use streaming video to present a particular topic to anyone who shows interest. All of this information and interaction comes at the cost of a serious time investment. I had the opportunity to visit the Vota Inteligente headquarters, a comfortable two-story house in residential Santiago, which was buzzing with eager volunteers who were adding information to the database and discussing how to improve the functionality of the website. While their enthusiasm and hard work was infectious, one must wonder if it is sustainable.

Unlike the dozens of volunteers that Vota Inteligente has managed to attract, KohoVolit.eu relies on the dedicated work of just two individuals who have managed to create a directory of profiles about every representative in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. It even includes fairly extensive information about the activities of representatives (MEP's) of the European Union. In our interview, project founder Michal Skop emphasized that the sustainability of parliamentary informatics websites depends on their level of automation. Any such website that depends heavily on human labor to input and organize information, Skop says, is likely to run out of steam. By taking government data and automating its presentation and distribution in new ways, the participants of such projects can spend more time on adding much-needed contextualization and analysis to the stream of information.

Automation, however, depends on the availability of properly structured, open government data that programmers can easily import and manipulate. Brazilian political scientist and co-founder of Congresso Aberto, César Zucco, says that the current transaction costs of seeking out congressional data across multiple websites in Brazil is so high that he and his colleague Eduardo Leoni have not been able to analyze any of the data they have collected. They are now waiting for the Brazilian government to implement the proposed Government Information Law, which should mandate government agencies to make official data available in structured formats that can be put to use by platforms like Congresso Aberto. Congresso Aberto was modeled on two other, similar websites: Open Congress (United States) and Vote Watch (European Union). It contains: 1) data and analysis about Brazilian Congress such as voting records and attendance; 2) profiles and information about representatives; 3) information about Brazilian political parties; and 4) proposed bills and legislation. The information comes from the official websites of Brazil's Congress, but it is not yet as timely and granular as Zucco and Leoni would like.

In fact, in terms of sustaining the movement of open parliamentary data, a strong argument could be made that activists should first work on implementing satisfactory government information laws – along the lines of the Open Government Directive in the United States – before working on information management systems to help bring that information to more citizens. Of course, it doesn't have to be one or the other, but analyzing and communicating the information does depend on having access to it.

In Kenya, Mzalendo is another platform which came into existence precisely because of the lack of official data from parliament. Ory Okolloh and her colleague Marc launched the project at the end of 2005 after the website for Kenya's Parliament was shut down following protests by some MPs who were embarrassed about having heir CVs published online. Kenya's parliament website is now back online – and much improved since its former 2005 incarnation – but Ory and Mark feel that they still have an important role to play in using online tools to hold Kenyan MPs more accountable. According to Mzalendo, the MP profile pages of the official Parliament website “are not working and the Hansards are still in pdf and not xml format, which makes them hard to repurpose.” The new (though not yet launched) version of Mzalendo, on the other hand, promises much more information and interaction. The Mzalendo blog has launched a new section called “Mzalendo Vox Pop” where guest contributors “discuss issues affecting their constituency in more detail.” Okolloh hopes that by the 2012 general election Mzalendo will have enough content to produce voter cheat sheets which rank incumbents by their participation and performance in parliament. The idea is to hand them out to voters without internet access who otherwise wouldn't be able to take advantage of the content from Mzalendo to make a more informed vote. “It’s one thing to tell people to make informed decisions, but that’s difficult when there is no information.” Still, like most of these sites, there are concerns about Mzalendo's sustainability. “We thought we could be sustained by volunteers, but that clearly is not working,” says Okolloh. “We think we are onto something good and potentially powerful, but how to build on it without becoming an NGO is a challenge.”

A hybrid model, which depends on volunteer students, but is able to count on the institutional support of the University of the Andes, is Congreso Visible in Colombia. As the websites of both Colombia's Senate and House of Representatives are hopelessly out of date, Congreso Visible depends entirely on students of the political science department of the University of the Andes to manually input the data about representatives, political parties, and legislative activity. There is also a useful section called the “Agora” that provides context, investigative reporting, and opinion pieces. Each quarter they publish a printed review of activity that took place on the website in order to distribute it to offline readers. As of today the website includes 1858 profiles of members of the Congress and aspiring candidates, 5614 legislative documents and almost 1144 voting records. Of all the parliamentary informatics websites we reviewed, Congreso Visible has the cleanest presentation, and might also have the most thorough inventory of information. It takes advantage of Flickr, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter to encourage interaction with the content published on the site. Colombia's Congress has contacted the Congreso Visible team to learn how to develop a similar website for the official Senate and House of Representatives domains. While the Colombian Congress should be applauded for seeking out expertise on how to modernize its information systems, this does beg the question, what will be the use of Congreso Visible if the Congress itself uses the exact same platform?

Most of the parliamentary informatics websites we reviewed seek to provide readers with more information about their representatives and how they vote. Others are more pro-active in encouraging citizens to think about issues rather than individuals. Vote na Web (“Vote on the Web”) is a tool developed by WebCitizen, which was launched in November 2009 at TEDx São Paulo. Using a clear interface, congressional bills are translated into simple language with clearly defined context and consequences. Beyond just explaining legislative bills in everyday language that most citizens can understand, the interface also encourages users to vote on the bills themselves, and then compare their votes with other users and with the politicians. So far most bills have only attracted between 10 – 500 votes, but if the number of users scales up, Vote na Web will provide an excellent visualization of just how representative Brazilian politicians are in their voting histories. KohoVolit.eu has also developed a number of online and offline applications to compare citizens’ votes with those of elected officials.

500 sobre 500 (“500 for 500″) also encourages more pro-active interaction by creating profiles of all 500 representatives of Mexico's House of Deputies, and then asking users to adopt each candidate and follow a list of updated “challenges”. The project ends at the end of the month.

Recommendations:

What stood out as most surprising throughout our documentation of all of these projects is that each one wrote an extensive amount of code to develop distinct platforms even though nearly all of the platforms follow the same basic structure: 1) profiles of representatives with voting records, 2) legislative bills, 3) profiles of political parties, 4) a section for context and analysis. We recommend that donors convene a meeting of technologists working on parliamentary informatics websites to agree on a single platform that can be used in all representative democracies. They should collectively develop and release the Ushahidi-equivalent for parliamentary informatics. So far OpenCongress, which is written with Ruby on Rails, backed by a PostgreSQL database and Solr full-text indexing, seems like the best bet. However, MySociety's TheyWorkForYou platform, written mostly in PHP, is another strong contender, especially for Commonwealth parliamentary systems that use a Hansard. The Congreso Visible platform, which was developed by Monoku and written in Django and jQuery is also worth further exploration, as is the Vota Inteligente platform, which is written in PHP.

[Update: We have since been informed by the Participatory Politics Foundation (developers of OpenCongress.org) that they are currently developing OpenGovernment.org, a new project that will make the open-source OpenCongress code base more modular and will be used to reveal state-, city-, and local-level government data. Its current code its hosted on GitHub.]

There is a lack of research comparing the practices and effects of parliamentary informatics websites. Arthur Edwards’ 2006 paper “Facilitating the monitorial voter: retrospective voter information websites in the United States, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands” is one of the few such studies, but it is by now outdated and limited in scope. Of specific value would be a quantified, comparative study of web analytics from each website. Where do visitors come from? What type of information are they seeking? Where do they spend most of their time? What parts of the website are frequently ignored? All of these questions can be answered with closer research into the web analytics of each website.

The majority of the projects we reviewed took advantage of social media services and relationships with their national blogospheres to distribute information and analysis from the website. We saw less evidence of collaboration, however, with civil society organizations and mainstream media institutions. A notable exception is Vota Inteligente, which has established an impressive network of like-minded national, regional, and international civil society organizations. They have also collaborated closely with mainstream media, such as CNN en Español to spread awareness and put pressure on politicians.

We recommend to project leaders that they thoroughly study search engine optimization and apply its strategies to their website development. Most users will likely arrive to their websites by searching Google for information related to a particular politician or keywords related to a legislative bill. It is crucial that the relevant page is among the first ten search results.

We recommend to project leaders that they work with local newspapers, radio stations, TV stations, and mobile phone service providers to distribute information and analysis from their websites to offline readers. Other strategies for offline distribution include Congreso Visible's model of quarterly reports and Mzalendo's plans for non-partisan voter pamphlets to be distributed before elections. We recommend that project leaders work in partnership with high school teachers to develop lesson plans that integrate these platforms into school curricula so that students understand the workings of their government from an information perspective. We also recommend to project leaders that in addition to scraping data from official parliamentary websites, they also take advantage of the wealth of contextual information found on sites like Open CRS, Parlio, and the National Congress Library of Chile in order to give a more thorough overview of how congress works.

We recommend to the Global Centre for ICT in Parliament that they reach out to technologists and administrators of parliamentary informatics websites to involve them in discussions and agreements related to XML and open standards in parliament. The 14-17 September 2010 Internet Governance Forum in Vilnius, Lithuania could be one potential venue to convene such a discussion.

We recommend to project leaders that they follow the strategy of Congreso Visible and partner with local universities to take advantage of eager students who can help input data into the system, and then analyze and distribute that information. We recommend to donors and universities that they facilitate more conversation between researchers of open government data and technologists working on parliamentary informatics websites.

We recommend to governments that they seek out the opinion of open government activists and technologists when deciding how to publish information online, and what information should be made available.

Thanks to Renata Avila for her contributions to this piece.

1 comment

Great stuff David, and let’s hope the GC4ICT in Parliament takes your recommendations!