A think tank for Japan's Cabinet, the Economic and Social Research Institute (内閣府 経済社会総合研究所) (ESRI) published a study that quantified the present status of lifetime employment and seniority-based wage (i.e. the Japanese employment system). They used the data (1989-2008) from Basic Survey on Wage Structure (賃金構造基本統計調査) (BSWS) of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The empirical results and commentary indicate a rare rebuke of the traditional employment system by the Government.

One of the results that they quantified was the “wage curve.” This is basically standardized median wages of workers according to the their age. ESRI showed that the wage curve “flattens out” gradually with time. This indicates that when young workers sacrifice some pay for a stable lifestyle in the future, they do not get as much value in the current state of affairs. The following is the graph: (please click to enlarge!)

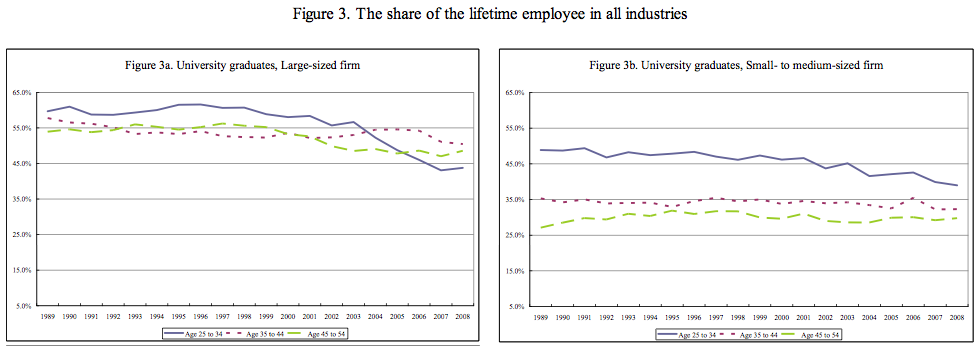

Now the second result comes from data of the share of lifetime workers for a company. The data shows a significant declining trend in young lifetime workers. This indicates lower retention rates of young workers and older workers staying in their old jobs since it is too risky to find another job. In particular, we see a large dip at year 2004 for the large firms, as that was the year the Government made it possible to use temp. workers in the manufacturing industry. This indicates that the continuance of the status quo may be unsustainable. The following is the graph: (please click to enlarge!)

Blogger, author and business consultant Jo Shigeyuki thinks it is significant that the Government finally admitted to the “collapse” (崩壊) of Japan's employment system. But he is also disgusted with the apathy and the patchwork solutions (like a cap on temp. workers) shown in an attempt to fix the system. Below he warns against a possible misunderstanding of ESRI's results:

賃金カーブの低下を指して「中高年も賃下げされている」と屁理屈を述べる労働組合関係者がたまにいるが、中高年は賃下げされたのではなく逃げ切ったというのが正しい。90年頃、「若い間は辛抱辛抱」と言い聞かせて頑張った元若者は、20年近く経って、かつての上司・先輩より3割以上も給料が安い結果に終わったということだ。

バブル崩壊後に、年功ではなく働きに応じて支給する仕組みにシフトしておけば、彼の生涯賃金はもう少し多かったろうが、そういう努力を怠ったということで自己責任というしかない。

さて、このように身をもって日本型雇用の破綻ぶりを演じてくれている世代がいるのだから、20代は同じ轍を踏まないように気をつけないといけない。というわけで、働きを基準としている組織に自分で移るか、それが出来るよう準備しておくことをおススメする

After the bubble burst, if the former young workers were able to adapt to a system that is based more on performance, their lifetime wages may have been better. But it is only the responsibility of those who didn't take the initiative to build a better system for themselves.

Now that there is a whole generation[s] of workers who experienced the degeneration of Japan's employment system, the current 20-somethings need to be careful not to fall into the same trap. So I recommend people to change or get ready to change jobs with an organization that value work.

Blogger, economist Ikeda Nobuo hypothesizes about the reason the Japanese people in general have a tendency to avert risk instead of hedging. The Japanese employment system was just a product of corporations that value stability:

[…]私の仮説は17世紀以降の株式会社のような有限責任の制度が日本になかったことが一つの原因ではないか、というものです。近代資本主義の成功をもたらした最大の要因が株式会社制度だったのではないか[…]

西欧圏でも株式は投機の手段として批判され、また現実にバブルや恐慌の原因となってきました。しかし資本主義を批判したマルクスは、株式会社制度を「生産の社会化」を進める制度として高く評価しました。これによってリスクが社会全体に分散されたことが、西欧圏の比類ない成長をもたらしたのです。

ところが日本では、株式を「銘柄」と呼ぶことでもわかるように、商品相場のような投機の対象として扱われ、戦前にはその9割が先物で、リスクは非常に高かった。株式が企業のリスクを分散する有限責任制度として活用されず、経営者は会社に無限責任を負い、会社がつぶれたらしばしば自殺します。他方、家計にとっては超ハイリスクの株式とリスクゼロの預金しかないため、ほとんどの人は危ない株には手を出さず、リスクを分散するという考え方も知らない。

In the West, shares of a stock were criticized as methods of speculation, and a cause for bubbles and financial panics. But when Karl Marx criticized capitalism, stock corporations were highly praised as a system for socializing the production process. Therefore, the risk was spread all over society as a key for unprecedented growth in the West.

However in Japan, joint-stock corporations were seen as brands and the commodity prices were looked at as tools for speculation; before the war, 90% of commodities were futures and the risk was very high. The shares of corporations weren't seen as tools for risk diversification and the companies held an infinite responsibility as they would kill themselves if something went wrong. For households, the only option was to hold extremely high risk stocks or no risk savings, so most of them chose the latter.

Blogger and MIT MBA student, Lilac reminds us of America a couple decades ago also faced similar problems of lowered competitiveness of certain firms (Kodak, Motorola, RCA). She ponders if it is better for large firms to reform itself or to collapse and start from scratch:

決して経営陣が技術を知らないバカなわけでも、技術者がツカえないわけでもないのだ。経営の舵取りを間違えただけで、これだけの技術と、研究者の努力が無駄になってしまう。大企業の組織を改変し、新しい技術に対応するように全体を変えていくのは、かくも難しいことなのだ。

「技術が優れてるから勝てる」わけではない、ということは、こうしてアメリカの企業たちは、日本企業やヨーロッパの企業に追いやられながら学んできていているのだ。

日本企業が、これらのアメリカ企業のように崩壊の一途をたどるか、IBMやGEがそうであったように再生するかは、今の経営の舵取りにかかっている。

It's not necessarily the case that better ideas and technology wins. The American firms have painfully learned a lesson from striving Japanese and European firms.

For Japanese firms to follow the path of Kodak et al. or the companies that successfully adapted to the conditions (GE, IBM), it all depends on a few decisions from the top that make or break a firm.

Blogger, IT worker elm200 proposes (facetiously) a solution that won't disrupt the vested interests that keep the status quo in Japan — to create an independent city that is the antithesis of the job conditions in Japan:

結局のところ、この国は現状維持を望む人が多いのだ。現状維持を望んでいる人々が多数派であるなら、どうして制度をいじる必要があるだろうか。一部の若者が騒いだところで、それより数が多い中高年や老人は現状に満足しているのだから、ガラパゴスだろうが鎖国だろうが、好きにさせてあげるのが一番だ。

好きにさせてあげるのだから、こちらにも一つくらいわがままを許してくれてもいいだろう。既得権益には何一つ接触しないので、疑り深い老人たちも何もいわないだろうし。

日本にシンガポールを作るのだ。

Because we're letting them be, it shouldn't be too bothersome of us to have just one selfish request. It won't touch upon the vested interests so the cynical old timers shouldn't have anything to say.

Let's build a Singapore in Japan.

Japan is in a gridlock. To reform the employment process, many people propose higher job mobility, which feeds entrepreneurism. Conversely, entrepreneurism is a decent indicator of job mobility. I wrote an article recently on entrepreneurship rates in Japan and found that it is very low relative to other countries.

Two interesting series that discuss the perils of employment currently in the media:

- Nikkei Business: “Cancelled job offers – This is why I was tricked” (「内定取消」-だから私は騙された)

- J-cast: “To you, who is 29 years old and working. It's not too late!” (29歳の働く君へ〜いまからでも遅くない!)

4 comments

I don’t think job mobility as such is a prime factor in promoting entrepreneurism. Job mobility implies ease of leaving a job and finding a new one.

Factors such as easy access to capital, and an independent spirit, are more important. A would be entrepreneur needs the cash and confidence to start out on his own.

The Japanese have a more collectivist, group-oriented social psychology and perhaps this makes them generally less entrepreneurial than Americans.