Ten years after the referendum, global voices are again spreading [1] the word for East Timor, but this time celebrating the strong international solidarity that back then culminated in the country's recognized self-determination:

On 30 August, 1999, hundreds of thousands of Timorese voters braved an Indonesian-directed terror campaign to cast ballots for independence in a U.N.-organized referendum. This event, which ended Indonesia’s 24-year illegal, brutal military occupation, led to the creation of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste as the first new nation of the millennium. The vote was the culmination of decades of struggle by Timorese people, supported by solidarity activists around the world.

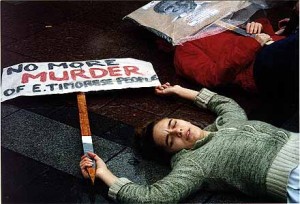

The release of journalist Max Stahl's video recording of the outrageous Massacre de Santa Cruz [2] in 1991 increased global awareness about the crimes occurring in East Timor under the Indonesian occupation.

In 1996 Jose Ramos-Horta and Bishop Ximenes Belo were awarded the Peace Nobel Prize and only three years later Indonesian President Habibie allowed the people of East Timor to choose between autonomy within Indonesia and independence. And the world united along with East Timor.

Solidarity movements able to pressure their governments and protest Indonesian abuses sprung up in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Portugal, France, Holland, Ireland, Germany, the UK, Canada and the US during the 1990s. Even within Indonesia, East Timorese had friends working to stop abuses and promote self-determination [4].

In the summer of 1999, in the lead up to the Referendum, the International Federation for East Timor [5] assembled the Observer Project, an international team of members from at least 22 countries to go to Timor and monitor the vote. The security arrangements for the months preceding the referendum were shaky, as the UN-brokered agreement for the Referendum left security to the Indonesian police.

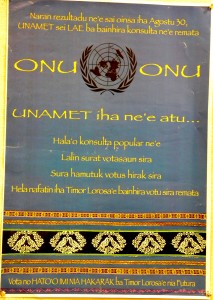

UN poster that reads "We will not leave" credit to Australia Timor-Leste Friendship Network

IFET monitors bravely fanned out across the territory, a project report from August 22, 1999 explains [6]

We have rented houses and deployed teams in every area of East Timor. Upon arriving in a town, an IFET-OP team first makes contact with the police and local authorities, and then with various community leaders and advocates on both sides of the campaign. They settle into a house which an IFET-OP advance team has arranged, and begin observing and inquiring about events and perceptions related to the campaign and other aspects of the consultation. Each team reports in nightly by phone and files a written weekly report. Although nobody on any of our teams has been injured, several have witnessed violent or intimidating incidents, and have reported such events to the appropriate authorities, UNAMET, and IFET-OP headquarters in Dili.

The IFET observers reported the violence that engulfed East Timor after the vote, which it turned out, was overwhelmingly for independence from Indonesia. The IFET Observer Project reported on September 3 [7]

The observers, members of the International Federation for East Timor Observer Project (IFET-OP), traveled to the Becora neighborhood of Dili to investigate reports of militia burning houses in the area yesterday. When they arrived, they found a house newly ablaze, and with both firefighters and journalists at the scene, the IFET-OP team went to investigate. Ten minutes after the observers arrived, the Indonesian military-backed militia showed up at the house.

The Aitarak (Thorn) militia struck one U.S. IFET-OP member in the face. Another team member, a woman from Finland, was hit in the back by a militia holding a gun. Yet another Finnish team member was threatened at gunpoint. The militia members also punched the IFET-OP driver and smashed a window on his car.

With militia violence kicking off again almost immediately after the vote, solidarity groups around the world began to demand their governments pay attention to the worsening situation in East Timor. The following video [8], from Jose Budha [8], portrays how Portugal stood up and stopped in that period:

[Subtitles] The images of a country standing for 3 minutes in solidarity with a distant people ran the world, as did the aerial view of a 10 kilometers human chain. Thousands ended up heading towards Madrid, so that they could shout loudly their rebellion against the Indonesian Embassy. Indonesia eventually accepted the entry of an international force in East Timor. The UN took another week to send this force. We do not know how many people died. Out of the 18 accused in Indonesia of involvement in the events of 99, only 1 was convicted and the others were acquitted in different instances. There is a certainty that in the future, when necessary, there are millions of voices ready to scream, reaching as far as 14,000 kilometers away, to Timor Lorosa'e.

After the results were out in the 4th of September numerous atrocities, killings and devastation happened as TAPOL reported [9]in 1999:

After the referendum results were announced on 4 September, the militias and their Kopassus bosses unleashed a scorched-earth policy of gigantic proportions. Para-military forces joined the fray, along with six TNI battalions, including two notorious local battalions, 744 and 745. Altogether about 15,000 men were involved. Without such a large contingent of men, it could never have taken hold so rapidly.

Although [Operation] Sapu Jagad-II sought to create the impression that this was a spontaneous outpouring of anger by pro-Indonesia forces, there is overwhelming evidence that the destruction was a well-prepared military operation. In many places, villagers were forced to destroy and burn their own neighbourhoods, even their own houses. The aim was to destroy as much as possible and punish the pillars of the pro-independence movement. The Catholic Church, which had given sanctuary to fleeing East Timorese throughout the occupation, was one of the main targets.

[10]

[10]Photo from "Genocide Watch: East Timor 1975-1999", researched and written by Adam Jones. Shared under a license for non-profit use.

All IFET OP volunteers were forced to leave Dili by September 7, 1999 under extremely harrowing circumstances [11]

Today, September 7, the last of our observers was forced to leave East Timor. Over the past two days, the Royal Australian Air Force evacuated 60 of our nonpartisan volunteers to Darwin from Dili and Baucau.

We left East Timor for safety, but with tremendous sadness. The East Timorese people have no Australia to run to, no place to hide from militia terror. Last night, Australia and Indonesian military officers prevented one of our East Timorese staff members from boarding the plane with us — and he faces an unspeakable horror shared by hundreds of thousands of his fellow East Timorese.

Most international observers and media fled East Timor before IFET-OP had to leave, and we were the last international NGO to leave. UNAMET has withdrawn from the entire country except Dili, where their communications and electricity has been cut off, and they are surrounded by militias who shoot into their compound virtually without interruption.

The mentioned “world pressure” became more and more real as citizens did not resign. Some photos of solidarity ties in Portugal may be seen in Tane Timor [12]website [12]. Maremargo [13]posted images from Spain. Antonio Jose, from Uma Lulik blog, illustrated and emotionally described what was happening in Lisbon in a never before seen solidarity during the 7th [14] and the 8th [15] [pt] of September 1999:

As sirenes dos bombeiros ouviram-se ininterruptas nesses 3 minutos… parámos por Timor-Leste como nunca parámos por mais nada… TODOS (…)

Durante toda a tarde do cimo daquele prédio foram lançados constantemente papeis e papelinhos, rolos de papel higiénico, tudo o que vinha à mão era material para protesto. No final da tarde percebe-se que esse stock acabou pois eram as páginas amarelas que fluíam nessa altura… aquele ventinho sempre a ajudar e a depositar os protestos em plena embaixada dos EUA, nas árvores, no seu jardim e envolventes. No topo do prédio viam-se gente de gravata e camisa, a causa era a mesma…

Throughout the afternoon from the top of that building, papers, little bits of paper and rolls of toilet paper were constantly released, everything that came to hand was material to protest. In late afternoon we found out that the stock had finished just because they were then throwing the yellow pages… the breeze was also helping us to send out the protests directly to the U.S. Embassy, in the trees, in its garden and surroundings. At the top of the building we saw men in suits, the cause was [the paper] …

[16]

[16]"Civil non-obedience for Timor Loro Sa'e" in front of the US Embassy in Lisbon, Portugal, September 1999. Photo by Flickr user nopasaran, used with permission.

While the East Timor Action Network put people on the streets in September 1999, it was also able to count on the phone calls and letters of over ten thousand Americans [17]

ETAN grew during 1999, enlarging our membership from 8,500 to 11,700. […] Using our experience and national activist network developed through eight years of dedication to a cause many called hopeless, ETAN mobilized public and official pressure. […] In September, ETAN’s web site was visited by more than 40,000 people a week. […] During September, our most active staff and volunteers were featured or quoted in countless mainstream media articles and programs, reaching tens of millions. ETAN activists authored op-eds in major U.S. newspaper, wrote letters to the editor, and appeared on local and national radio and TV shows.

On the other side of the world, the decisive moment for international intervention happened on the eve of the APEC summit in New Zealand, when Bill Clinton privately met with Pacific leaders. Only days prior he had announced the suspension of US military training with Indonesia. According to blogger Nigel Morley of “Writing for the Future [18]“

To some readers this may seem fanciful but when Timorese Nobel Peace Prize winner José Ramos-Horta met United States (U.S.) President Bill Clinton at the APEC meeting in New Zealand in 1999, Clinton remarked that Ramos-Horta had more influence with Congress than he did (Zubrycki: 2002).

New Zealanders turned out in numbers to welcome Clinton, Ramos Horta and Australian Prime Minister Howard. Australians also “Take To The Streets Over East Timor”: [19]

Banners saying “Stop The Slaughter” and “Wiranto – Murder.” Chants of “Free East Timor” and “Viva Timor Leste” (long live East Timor) came from the crowd after it heard from East Timorese resistance leader Mr Jose “Xanana” Gusmão during a live telephone hook-up from Jakarta.

“We need you, brothers and sisters of Australia, we need your voice,” Xanana Gusmao in Jakarta said by telephone, “I think it is important to send a message to the Indonesian Government that the Australian community and Australian workers will do everything they can to stop the killings. Viva East Timor,” he said. “Viva,” the crowd yelled back.

[21]

[21]Students from Kingsgrove High School pledge their support for a free Timor in 1999. Photo by Flickr user sHzaam!, used with permission

During the torturous days of September 1999, world leaders moved slowly to intervene in East Timor, when it was clear that the Indonesian military and its proxies were completely destroying the territory, and setting off a humanitarian crisis of massive proportions. But the decisive protest and advocacy of groups of concerned citizens across the world shamed the US, Australia, and Indonesia into turning a new page for East Timor.

A decade later, it is time to celebrate that global union. Several events [22]are scheduled in Dili, such as a photo exhibition in Fundação Oriente (which was itself the place where a massacre [23] occurred in 1999) describing solidarity movements over the years.

This is the first in a series of posts to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the popular referendum in East Timor, a vote which led to the territory's internationally recognized independence. If you would like to share memories from the acts of global solidarity for East Timor in 1999, please do so below.