Last weekend, Semana news magazine revealed that some agents at the Administrative Security Department (DAS for its Spanish initials), Colombia's “secret police,” had been illegally wire tapping politicians, journalists, magistrates, intellectuals, and —this time— even government officials close to President Álvaro Uribe, including his private and legal secretaries, and an official from his personal security staff. Even worse, according to the magazine, some of these agents allegedly had been “selling to the highest bidder,” namely guerrillas, paramilitaries or drug traffickers, the information obtained with the illegal phone bugging. Most of the recordings, the magazine says, were destroyed [es] between January 19-21. The story was echoed [es] early Saturday by other media as the magazine was hitting the stores.

On Sunday, agents from the Technical Investigation Corps (CTI for its Spanish initials) of the Attorney General's office raided DAS headquarters, causing a conflict [es] between both institutions. Later, the first high-rank DAS official was fired. Supreme Court issued a communiqué [es] demanding results from the Attorney General. Opposition accused the government for the tappings. A case of e-mail hacking has been denounced [es]. President Uribe denied it, claimed he is also a “victim,” and blamed it on a “mafia gang inside” the DAS. Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos said he wanted the intelligence agency to be disbanded, but the government itself disagreed [es] with him.

Wire tappings (or ‘chuzadas’ as they are known colloquially in Colombian Spanish) are not new in President Uribe's administration. In May 2007, the same magazine published recordings of paramilitary bosses in jail talking about committing crimes, and later more illegal wire tappings, by an elite police intelligence unit, were learned. As a consequence, Uribe dismissed 14 police generals, making Gen. Óscar Naranjo the new (and current) national police director. In late 2008, leftist senator (and former M-19 guerilla fighter) Gustavo Petro denounced he and his party were being ‘shadowed’ by people from DAS since August and published two internal memoranda issued by a DAS section chief. Its director and the mid-rank official who ordered the ‘followings’ resigned. In both cases, the government denied any involvement.

Both Sentido Común and Charly write about Uribe's words on the scandal. Sentido Común [es] worries about our national security:

De corroborarse la reiterada tesis de Uribe sobre la existencia de una mafia al interior de su gobierno, se estaría evidenciando la impotencia gubernamental para controlar cabalmente los cuerpos secretos del Estado, situación que estaría exponiendo al país a un estado de indefensión en materia de seguridad en diferentes flancos y con la gravedad que implica la convivencia con organizaciones mafiosas, enquistadas dentro del propio Gobierno.

Meanwhile, Charly [es] seems quite distrustful of the government and asks who is behind all this:

No me como el cuento que funcionarios de mandos medios del DAS actúen solos y que el Gobierno sea víctima de un complot. Estamos ante escándalos de mayores proporciones que, sumado al caso de Noguera y al de la Dipol (que tumbó a varios generales) evidencian una crisis de la democracia, un atentado contra el pensamiento y la libre opinión en Colombia.

Valentina Díaz makes some questions [es] at Realidades Colombianas:

La presidencia de la república niega, el Director del Das hace lo mismo. Ninguno de los mandos ni jefes del servicio secreto a disposición del Presidente de la República ha ordenado escuchar a un grupo selecto de personas no adeptas a su gobierno. Pregunta: ¿Acaso, al interior del Das cada cual hace lo que se le viene en gana? ¿Se trata de gente desbocada y sin control superior? “Según información que me han dado, hay conversaciones que están ahí y eso es muy grave”, dice el jefe del Das. En otras palabras, muchos saben de la intercepciones telefónicas, son dominio público, solo lo ignoran el presidente y el Jefe.

And Carmen Posada mocks President Uribe's “paranoia” [es]:

De acuerdo con Orwell, el Gran Hermano nos vigila todo el tiempo. Ya no podemos ni siquiera tirarnos un pedito sin que Uribe esté enterado, los que usamos la web ya no podremos siquiera mandarle un mensajito calentón al novio porque este degenerado va a pensar que estamos haciendo terrorismo virtual en mensajes cifrados.

No le creo ni media palabra a Uribe en el tema de las chuzadas de los teléfonos, no lecreo que no haya dado la orden aunque no exista una sola prueba de ello y no le creo porque el único interesado en seguir los pasos de la oposición es él que como buen estratega delirante es, además, paranoico.

I don't believe half a word that Uribe says regarding the phone bugging issue, I don't believe he didn't give the order no matter there's not even one evidence of it, and I don't believe him because the only one interested in following the opposition's steps is him, who is a good delirious strategist and, besides that, paranoid.

But journalist Jaime Restrepo, on Atrabilioso [es], justifies the wire tappings because of the ongoing internal armed conflict, and attacks [es] some media outlets which also have published stories based on phone buggings:

En medio de un conflicto interno como el que vive Colombia, la investidura de político opositor, periodista o jurista es accesoria, pues en muchos casos son fachadas para ocultar acciones criminales en contra del Estado y por supuesto, contra la administración que lidera un bando en el conflicto.

En ese orden de ideas, mal haría el gobierno en renunciar a la potestad de investigar a aquellos ciudadanos que pueden desestabilizar al país mediante apoyos y manejo de información que beneficie al bando que intenta subvertir el orden y llegar al poder por una vía diferente a la democrática.

Pero aquí hay más de fondo: en Colombia, los grandes beneficiados de las interceptaciones telefónicas han sido los medios de comunicación: Noticias Uno y Semana, entre otros, han liderado la publicación de escándalos basados en grabaciones obtenidas mediante interceptaciones ilegales.

Amidst an internal [armed] conflict as the one happening in Colombia, the labels of opposition politician, journalist, or jurist is secondary, because in many cases they are just façades to hide criminal actions against the State and, of course, against the administration which leads one of the sides in the conflict.

Things being so, the government would be wrong if it relinquishes the legal authority to investigate those citizens who might destabilize the country through the support or use of information benefiting the side which tries to subvert the order and reach the power through a way other than the democratic one.

But there's something deeper down here: in Colombia, those that are benefit from phonebuggings is the media: Noticias Uno [a nightly weekend newscast] and Semana, among others, have been leaders in publishing scandals based on recordings obtained through illegal wiretappings.

Mr. Restrepo also questions the way Semana obtained the information from some DAS agents, how they are trusted by the magazine with apparently few or no evidence, and even some of the claims made in the article. He believes there are doubts and that it might be a “carefully prepared” set-up against the government.

French journalist Jacques Thomet, AFP's former editor-in-chief, compares [fr] the scandal in Colombia with François Mitterrand's France in the 90s:

Comme peuvent le constater en France ceux qui qualifient de fasciste le régime de Bogota, […] les médias disposent en Colombie d’une liberté d’expression supérieure à celle en vigueur …en France.

Sous le régime socialiste de François Mitterrand, plus de 3.000 écoutes illégales ont été réalisées dans mon pays contre des journalistes et autres personnalités de 1983 à 1986 par la cellule anti-terroriste créée par le président français dans les locaux mêmes de l’Elysée ! Le résultat ? La presse n’en a parlé qu’en 1993, Mitterrand a éjecté trois journalistes belges qui lui avaient posé la question, et les coupables n’ont été condamnés qu’à des amendes. (…) La république bananière, elle se trouve à Paris ou à Bogota ?

Under the François Mitterrand's socialist regime, more than 3,000 illegal phonebuggings were carried out in my country against journalists and other personalities between 1983 and 1986 by the anti-terrorist cell created by the president inside the Elysée itself! The result? The press only mentioned the issue in 1993, Mitterrand expelled three Belgian journalists who asked the question to him, and the guilty were just fined. […] The banana republic, is it located in París or in Bogotá?

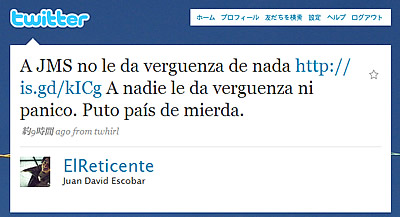

But at the end, @ElReticente sums it up, with scepticism, disappointment, and anger on this tweet [es]:

And, in spite of some dismissals and the media frenzy, as in the other scandals it is likely nothing will happen after a few days or week, despite the fact that some people are comparing [es] this issue with Alberto Fujimori's regime in Peru back in the 1990s. Another scandal, another attack, another murder, or another controversy involving Uribe, FARC, the opposition, or anyone else, will hit the headlines and become the talk of the day in Colombia.

6 comments

COLUMBIA IS THE ISRAEL OF SOUTH AMERICA USA’S LITTLE WIND UP TOY THE CLICK YOUR HEELS REGIME

http://www.smudailymustang.com/?p=8448

Is wiretapping an invasion of privacy or a right to gain information? One would want to know.