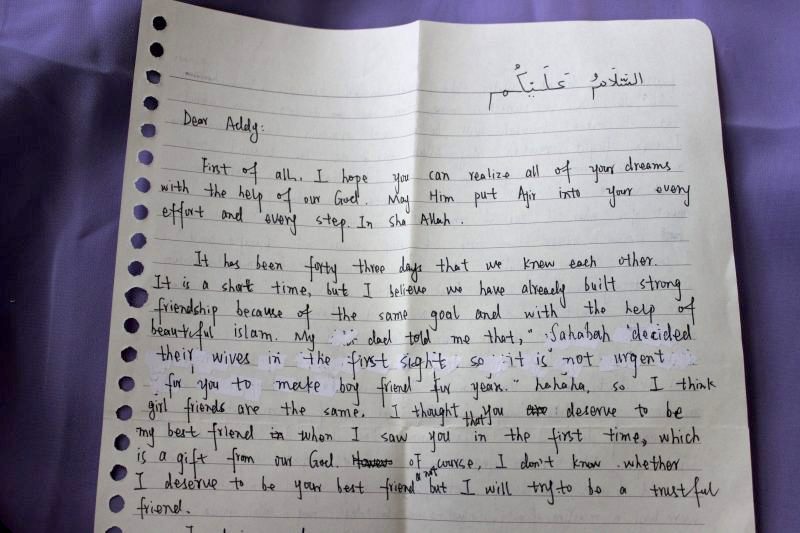

Letter from Zainur Turdi to the author. Photo by the author.

When I first came across the Xinjiang Victims Database, I clicked through maybe 100 testimonies. I took note of the testifiers and their relationship to the victim. Mother. Brother. Cousin. Niece. Family members. So many family members. Neighbor. Friend. Friend. Friend. Memories fogged my thinking, of people I knew who were detained. Of friends who were missing. Of people whose names I carelessly failed to remember. Of people whose names I mention in every prayer.

I thought I did not have sufficient information on anyone I knew to write a testimony. I knew no last names*. No Chinese ID numbers. But in packing up my apartment recently, I took a moment to open again the letters I had received from friends when I left Beijing in May 2017. Zainur (“Zeynur” in standard Latinization) penned the longest of these letters. The day I left, she sat holding my hand outside of my dorm. Other students from my program shuffled about, lining up their luggage, saying goodbye to friends. Zainur said almost nothing. When I stood to board the bus, she pressed the letter to my palms, kissed my cheek, and ran. I would later learn that she returned to her own dorm in tears. Meanwhile, I sat on the shuttle to the airport quietly crying. It was my 21st birthday.

Letter from Zainur Turdi to the author. Photo by the author.

We had known each other for 43 days. She says so in her letter. She had counted. A mutual Uyghur friend had introduced us, and we became rather inseparable from then on. So much of our friendship revolved around prayer. Even with sanctuaries as rare as they are in China, Zainur, like so many other Uyghurs desperately clung to any semblance of the sacred. Most times she would mime the gestures of prayer wherever she sat or stood.

Sometimes she dared to go through the actual motions in their entirety, once I assured her it was safe. And sometimes I watched as she hesitatingly mimicked the positions of ruku and sujood, bowing and prostration, with her finger. Her finger. One evening while on the train, she rested her head upon my shoulder and began to mumble al-Fatihah, the first chapter of the Quran, squeezing my hand for every change of position. She later told me how at home in Xinjiang, in the city of Kashgar, for every salah, or daily prayer, she sought out her mother and did the same.

“My mother is my masjid,” she told me. “Maybe sisters are the next best thing.”

Letter from Zainur Turdi to the author. Photo by the author.

Yet of everything I remember she told me, I do not remember her voice. I have one photo of her, shrouded in black, praying, her face turned away from the camera. The only personal effect I have from her is this letter and one sentence. I remember only one sentence in her voice: “I don’t know why.”

Padlock on the door of a mosque in Beijing. Photo by author.

She said it often when she would tell me about what was happening in her home town. They barred women from the masjid. They scanned the faces of anyone who entered the masjid. They scanned faces at markets and airports. They banned the hijab. They banned fasting. Neighbors are disappearing. Cameras are everywhere. We buried our books. They told us to remove the locks from our doors. They took my passport. “I don’t know why.”

Letter from Zainur Turdi to the author. Photo by the author.

One year later, in June 2018, I returned to Beijing. I landed the night before Eid. I removed my hijab, knowing full well that, without hijab, I had the advantage of being nothing more than an American with an English name. That way, I could better seek out Uyghurs I knew. I attended Eid prayer alone, with my hair in a braid, a scarf loosely thrown over my head. Only one year prior, I had attended this mosque each week with a crowd of Uyghur friends. On Eid 2018, there stood outside only a crowd of policemen, checking the identification documents of a trickling of Hui people and foreigners who entered. They inspected my passport. They studied my face. They waved me away. I would try to go to a mosque only once more during that trip. I would find the doors shuttered and padlocked. Signs indicating the structural integrity of the building was a hazard.

One old Uyghur friend was still at university, awaiting graduation. She knew she would be sent to a camp if she could not find a job. She mentioned her siblings. Prisons now claimed all of her brothers. Camps swallowed up a sister, cousins, and friends. Forced labor. Factory work. Police work. Disappearances. Unknowns. Some knowns. Zainur?

Zainur has been in a detention camp since July 5, 2017.*

* The information was confirmed to the author by multiple sources familiar with Zainur's situation. Her full name has been confirmed as Zainur Turdi.

The Xinjiang Victims Database is the largest searchable English-language database relating to victims of the ongoing repression in XUAR. Global Voices welcomes testimonies from friends and relatives of people who are victims of state repression in XUAR.